Remembering Bergman

Bergman was very fond of the Faroe Islands, the island of sheep. With the death of his wife Ingrid von Rosen, he was alone with only the sheep of the island.

Written by C V Balakrishnan | Updated: June 24, 2018 11:12:52 am

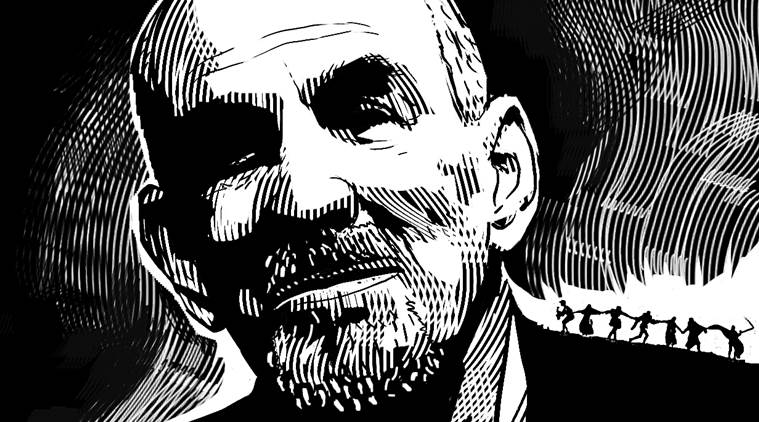

Bergman was not influenced by the Russian film theory or Italian neorealism or the French New Wave. (Illustration: C R)

Ingmar Bergman was different from his filmmaker contemporaries. He was concerned with presenting through his films the mysteries of human existence. We may say that the God who created humans has not had a greater critic, or an adversary even, than Bergman. He did not deny the existence of God, but raised doubts about Him with his relentlessly questioning mind; it was like knocking ceaselessly on a door that he knew would not open.

Bergman was not influenced by the Russian film theory or Italian neorealism or the French New Wave. His oeuvre cannot be compared stylistically to filmmakers who had behind them a clear ideology, like Sergei Eisenstein, Vittorio de Sica, Roberto Rossellini, or Jean-Luc Godard. His cinema had no politics in it. His existential and metaphysical uncertainties were reflected in his work.

Bergman was elevated to the upper echelons of world cinema after his 1956 film, The Seventh Seal. I watched this two decades later. This was my first Bergman film — an unforgettable experience. What The Seventh Seal gave us was a dark dream, inhabited by the pessimistic fate of man in a world abandoned by God. I had never seen death in concrete form before that. Against the backdrop of a land brought down by a plague, Bergman reveals to us, as if in a nightmare, man’s appetite for life, his helplessness, his vulnerability, his despair. Both the premise of the narrative as well as the cinematographic play of the opposition of light and dark induce in the viewer this same sense of anguish. The dance of death towards the end of The Seventh Seal is one of the most memorable scenes in cinema.

I was touched as much by his Wild Strawberries (1957), a film that seeks the truth of human nature and relationships. Dreams and memories lie entwined in this work. Structured around a road trip, the film is a journey of self-inquiry by an old man, Isak Borg. The different stages of the journey are revealed through a series of dreams and memories. The substance of the narrative is in the self-knowledge that the central character gains through his journey in the present and through the past. This self-knowledge was significant for Bergman.

Women characters were a major presence in Bergman’s films. They were portrayed in detail and with empathy. His Cries and Whispers (1972) dives deep into minds that are filled with irrational fears, suppressed desires, adamant feelings of guilt and the thirst for revenge. Agnes, who is battling uterine cancer, her sisters Karin and Maria, and their maid Anna are the main characters in the film. They live on an estate in the country and have little contact with the outside world. Their only visitors are the priest and the doctor. Death is an invisible but ever-present guest. The Bergman corpus is an artistic protest against mortality and in Cries and Whispers this philosophy is best established. The magic that cinematographer Sven Nykvist creates with colours adds to the aura of the film.

The long creative collaboration between Nykvist and Bergman is reported to be one of the most illustrious in the history of cinema. In their first film together — Sawdust and Tinsel (1953) — Nykvist was one of three cinematographers who worked with Bergman. Their next collaboration was the Academy Award-winning The Virgin Spring (1959). Nykvist had commented that it was Bergman who made him understand the endless possibilities of cinematography: “I owe a great debt to Ingmar, for he gave me my passion for light. Without him I would have remained just another technical cameraman… I learned so much about composition, staging, and the infinite varieties of light from Ingmar… He has a mind and an imagination that takes in not only the limits of poetic imagery, but equally the scientific aspects of filmmaking. He has done away with ‘nice’ photography and has shown us how to find truth in camera movement and in lighting….”

Bergman and Nykvist communicated through a private language; without uttering a word. They were of one mind. The cinematographer won two Academy Awards for his Bergman films (Cries and Whispers, Fanny and Alexander). However, it may be that Bergman’s relation to theatre was closer than his relation to cinema. From his intimate familiarity with both forms, he arrived at a curious conclusion: “The theatre is like a loyal wife, film the big adventure, the expensive and demanding mistress — you worship both, each in its own way.”

I remember the anxious wait outside a cinema theatre in Bombay during an international film festival to watch Fanny and Alexander. Sitting next to me was the acclaimed Malayalam writer and director P Padmarajan. There was a rumour that Bergman himself would be present for the screening. However, it was his friend and collaborator, actor Erland Josephson, who appeared on his behalf. Sadly, Bergman never came to India. At the end of the film, Padmarajan remarked to me: “What a thrilling experience!”

Bergman was very fond of the Faroe Islands, the island of sheep. With the death of his wife Ingrid von Rosen, he was alone with only the sheep of the island. This lonely island was full of dark dreams. Bergman died in his 89th year. What would have been the last dream that the cinematic maestro had seen?

Balakrishnan has written over 60 books and won the Kerala Sahitya Akademi award twice. His novel Ayussinte Pustakam (The Book Of Life) is considered a modern classic. He retired as a school teacher and now lives in a village in Kasaragod district in Kerala.

Translated from Malayalam by Gautam Das.

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario