The skew in education

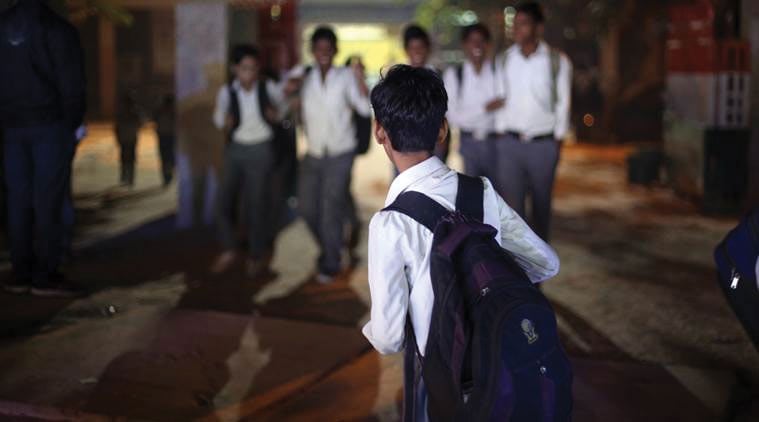

Poor quality government schools make higher education out of reach for non-elite . That’s the real problem, not public-funded universities.

The phrase, “let the elite pay” refuses to acknowledge that if the government schools continue to be of poor quality, the non-elite will always find it difficult to reach higher education.

In his article, ‘Let the elite pay’ (IE, June 23), Surjit Bhalla argues for the continuation of the highly discriminatory school and higher education systems that already provide education to most on the basis of ability to pay. He acknowledges that “children of the poorest of the poor”do not receive basic quality education and hence cannot compete with children of the rich. However, Bhalla refuses to question the existence of an unequal schooling system.

Why does the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act 2009 not guarantee equal “quality” education to all? Why does it allow private schools to put a price tag on quality education? Why does it allow only restricted access to quality government schools like the Kendriya Vidyalayas? Bhalla informs that in India, “the average good quality high school education costs more than five times the average good quality college education. In most civilised economies, the ratio is the opposite”. But this is precisely because in these countries, the state takes responsibility for school education. In Sweden, Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway and Canada, the enrollment in state-funded schools is as high as 80 per cent to 95 per cent. Should we not also demand quality government school education in India, thus making it a preferred option? The proposed voucher system is no alternative to the state taking responsibility for providing free and quality education to all. A voucher system legitimises and reinforces the idea that, instead of being a “public good”, school education is a commodity for sale. If the state is to provide vouchers that can be claimed by private schools, why should it not instead invest in enhancing the quality of state-funded schools. Government schools cannot be given the option to “perform or perish”. They must be supported to perform.

Bhalla goes on to term affirmative action in higher education as “non-merit” interventions. He rues, “… at premier institutes like IIT, if the average admissions score for a general category student is X, for the reserved SC/ST category it is half X. The evil market being what it is, what are the much below average students going to do when they graduate?” This is a problematic understanding of “merit” and “aims of education”. Suddenly, the denial of quality education to the marginalised is forgotten and the blame shifted from poor quality schools, which failed the students, to the students themselves. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds face greater challenges in clearing IIT JEE and NEET because of the inability of our school curricula to meet the demands of these entrance examinations, and hence the reliance on extremely expensive coaching institutes. Where this double disadvantage does not exist, the figures can be different. Sample the cut-offs from St Stephen’s college this year: BA Economics General-98.75, SC-95.75, ST-92.75; BA English-General- 98.5; SC 97.5; ST-97.5.

Also, what makes IITs “premier institutes” if they cannot be entrusted to instill any further skill in the students? As a teacher, I refuse to accept the idea of education as one that promises nothing and refuses to engage with students, does not empower them or challenge the inequalities in society. Bhalla’s jibe regarding the market rejecting these students who can find jobs only in the government sector that a “perfect Indian system will reward them with”, suggests his disdain for the idea of a socially-inclusive India that assures jobs to sections who have historically been deprived of education and employment opportunities.

The phrase, “let the elite pay” refuses to acknowledge that if the government schools continue to be of poor quality, the non-elite will always find it difficult to reach higher education. Instead, public-funded higher education institutions, already being pushed to generate their own income, will be encouraged to prefer those who can pay. It is important to remember that students from socially and economically disadvantaged sections continue to face disadvantages in higher education. The increase in suicides among students coming from these sections is alarming. Far from supporting these students with English language, academic writing and other skills, institutions demand these skills from them.

When covert discrimination continues in conditions of same fee for all, one can imagine the entitlement battles when only some are asked to pay. This is already seen in case of several children from BPL families who make it to private schools due to an RTE provision guaranteeing 25 per cent reservation in aided private schools. Their accounts reveal stories of humiliation, neglect and insensitivity, forcing several to drop out. In public-funded higher education institutions, already grappling with fund-cuts, infrastructural inadequacies and shortage of faculty, what will stop those paying more from claiming higher entitlement to scarce resources?

There exist enough private schools, and now an increasing number of private universities, for those willing to pay. Let the educational spaces that remain equal and socially just, be kept away from the forces and logic of Bhalla himself terms, “the evil market”.

The writer is assistant professor, School of Education Studies, Ambedkar University, Delhi

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario