A spectre not yet laid to rest

Events of 1984 still scar the Punjab mindscape. A People’s Commission and a Peace Memorial are needed.

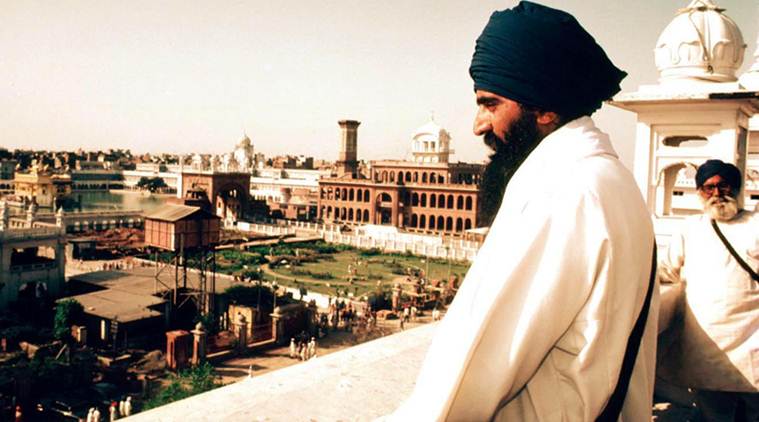

Bhindranwale at the rooftop of the Sarai in Golden Temple Campus before Operation Blue Star in Amritsar. (Express Archives/Swadesh Talwar)

The people of Punjab suffered indescribable hardship and trauma due to the chain of events culminating in Operation Blue Star in June 1984. The aftermath also left a trail of violence and misery, bitterness and alienation. Such periods invariably generate polarised perceptions and ideological stances.

But more than three decades later, Operation Blue Star has become a symbol of tolerance, harmony and peace-building. Its memories have introduced restraint when the state confronted similar situations later, be it when terrorists entered the shrine of Hazratbal in Srinagar or when attempts were made to condone the demolition of the Babri Masjid. It can be safely inferred that had the deadlier politics manifesting in Operation Blue Star, assassination of the then prime minister and Sikh massacre, not been unleashed, terrorism may have petered out in 1985.

The churning in civil society and politics has led to a positive outcome. The hurt felt by members of the Sikh community and secularists became universal. It transcended the boundaries of religion, region, political and social affiliations. It has blemished the stature of leaders like Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. If Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale could not become an unquestioned icon of the Sikh masses, the legacy of the former Indian prime ministers responsible for Operation Blue Star and November 1984’s brutal targeting of Sikhs has also been tarnished.

More than three decades later, Operational Blue Star has also outlived the relevance of superficial apologies and the documentation of painful memories. The state has been shying away from fixing responsibility for the creation of conditions leading to Operation Blue Star. It has resorted to offering apologies without accountability.

Leaders and decision-makers responsible for causing violence conveniently tender apologies and consequently cause delay in the accountability processes. Punjab has witnessed this phenomenon in an aggravated form. For example, a section of political leaders responsible for the creation of conditions leading to Operation Blue Star in 1984, and the killings of Sikhs in November 1984, indulged in the politics of apology without accountability. The state has lacked seriousness in bringing people responsible for Operation Blue Star and the violence against Sikhs to justice.

This has led to the setting up of a number of committees and commissions of inquiry without delivering justice. It started with the Ved Marwah inquiry which was wound up without completing its report in 1985, followed by the Dhillon Committee in 1985, Ahuja Committee in February 1987, Jain-Banerjee Committee in February 1987, Jain-Aggarwal Committee in December 1990, Narula Committee in December 1993, Ranganath Mishra Commission in May 1985 and the Nanavati Commission in May 2000. The politics of inquiry commissions must be given a burial.

Elections to state assemblies and local bodies have been held. Religious, non-governmental organisations and the government have provided assistance to victims of the violence. A conducive political climate was created for the return of former militants like Wassan Singh Zaffarwal of Khalistan Commando Force from Switzerland on April 11, 2001. Jagjit Singh Chauhan returned in 2001 after 25 years of exile.

Elections to state assemblies and local bodies have been held. Religious, non-governmental organisations and the government have provided assistance to victims of the violence. A conducive political climate was created for the return of former militants like Wassan Singh Zaffarwal of Khalistan Commando Force from Switzerland on April 11, 2001. Jagjit Singh Chauhan returned in 2001 after 25 years of exile.

In a way, it weakened the divisive and separatist politics, but delayed initiatives for closure have provided a new lease of life to extremist and fundamentalist political tendencies. After having ignored twice the appeal of Dal Khalsa, a radical Sikh organisation, in 1985 and 2002 to raise a martyr’s memorial at the Golden Temple, it was conceded by the Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC) in 2014.

We also witnessed the ceremonious conferment of martyrdom to Bhindranwale by the SGPC after 19 years. It is mainly because no concerted efforts were made to delegitimise violence and deliver restorative justice. The goals of closure — transparency, justice and reconciliation — were not addressed adequately.

Closure does not mean revenge. It also does not mean the registering of a claim that “my” use of violence is privileged and therefore cannot be brought to justice. The main focus of closure should be recognition of the atrocities committed and willingness to live with truth. This may involve setting up of documentation centres, museums of memories etc.

Efforts should be made to build a Peace Memorial, a monument in the memory of those who became victims of decade-long terror. The setting up of a People’s Commission is the need of the hour. Justice and reconciliation cannot be delivered unless preceded by transparency. Excessive use of violence led to the defeat of Khalistanis but at the same time excesses unleashed by the state increased support for their ideology. Legitimacy of both the state also declined due to the violation of human rights and it is in its own interest to evolve codes of conduct for peaceful closure. The Commission should fix responsibility for the unleashing of a deadly politics manifesting in the killing of innocents, security personnel and political activists.

The focus of closure should be the delegitimisation of violence, the reducing of incentives to violence and delivery of restorative justice and reconciliation.

The writer is director, Institute for Development and Communication (IDC), Chandigarh

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario