Four reasons why Indira Gandhi declared Emergency

The trouble began in Gujarat, spread to Bihar and from there to several other parts of Northern India.

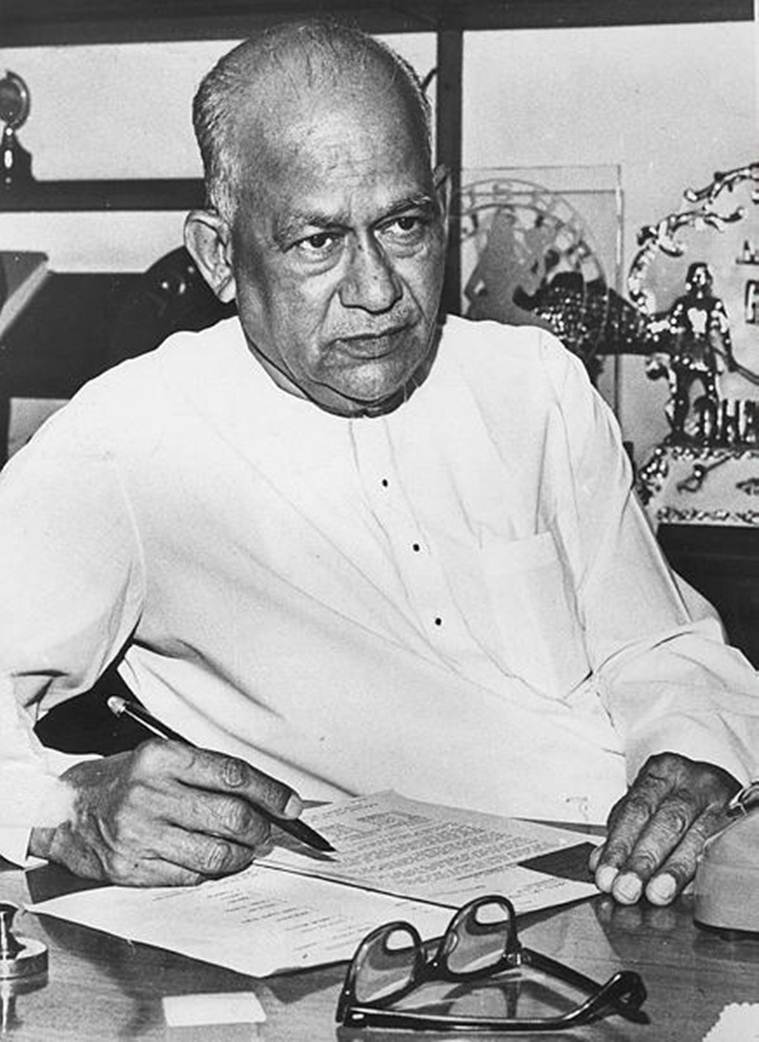

The proclamation of Emergency had been signed by President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed on June 25, 1975 (Expres archive photo)

“The President has proclaimed Emergency. There is nothing to panic about.” The words of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi blared from the All India Radio in the wee hours of June 26. The nation, on the receiving end of this piece of news, was as unsuspecting of it as were Gandhi’s Cabinet ministers who had been informed just hours before the PM proceeded to the AIR studio. The proclamation of Emergency had been signed by President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed the previous night itself. Soon after, newspaper presses across Delhi sank into darkness as a power cut ensured that nothing could be printed for the next two days. In the early hours of June 26, on the other hand, hundreds of political leaders, activists, and trade unionists opposed to the Congress Party were imprisoned.

The goal of the 21-month-long Emergency in the country was to control “internal disturbance”, for which the constitutional rights were suspended and freedom of speech and the press withdrawn. Indira Gandhi justified the drastic measure in terms of national interest, primarily based on three grounds. First, she said India’s security and democracy was in danger owing to the movement launched by Jayaprakash Narayan. Second, she was of the opinion that there was a need for rapid economic development and upliftment of the underprivileged. Third, she warned against the intervention of powers from abroad which could destabilise and weaken India.

The months preceding the declaration of the Emergency were fraught with economic troubles — growing unemployment, rampant inflation and scarcity of food. The dismal condition of the Indian economy was accompanied by widespread riots and protests in several parts of the country. Interestingly, the hitherto simmering borders of the country were rather quiet in the years preceding the Emergency. “As if to compensate, there was now trouble in the heartland, in parts of the country which, for reasons of history, politics, tradition, and language, had long considered themselves integral parts of the Republic of India,” writes historian Ramachandra Guha in his book, ‘India after Gandhi.’ The trouble began in Gujarat, spread to Bihar and from there to several other parts of Northern India. While the streets were raging against Gandhi’s governance, another challenge came to the doorstep of the prime minister in the form of a petition filed in the Allahabad High Court.

Here are the four major occurrences of the 1970s following which Indira Gandhi declared the Emergency.

Navnirman Andolan in Gujarat

In December 1973, students of L D College of Engineering in Ahmedabad went on a strike to protest against a hike in school fees. A month later, students of Gujarat University erupted in protest, demanding the dismissal of the state government. It called itself the ‘Navnirman movement’ or the movement for regeneration. Gujarat at this point in time was governed by the Congress under chief minister Chimanbhai Patel. The government was notorious for its corruption, and its head popularly referred to as chiman chor (thief).

The student protests against the government escalated and soon factory workers and people from other sectors of society joined in. Clashes with the police, burning of buses and government office and attacks on ration shops became an everyday occurrence. By February 1974, the central government was forced to act upon the protest. It suspended the Assembly and imposed President’s rule upon the state. “The last act of the Gujarat drama was played in March 1975 when, faced with continuing agitation and fast unto death by Morarji Desai, Indira Gandhi dissolved the assembly and announced fresh elections to it in June,” writes historian Bipin Chandra in his book, ‘India since Independence.’

The JP movement

Following in the footsteps of Gujarat or rather inspired by its success, a similar movement was launched in Bihar. A student protest erupted in Bihar in March 1974 to which opposition forces lent their strength. First, it was soon headed by 71-year-old freedom fighter Jayaprakash Narayan, popularly called JP. Second, in the case of Bihar, Indira Gandhi did not concede to the suspension of the Assembly. However, the JP movement was significant in determining her to declare Emergency.

A hero of the freedom struggle, JP had been known for his selfless activism since the days of the nationalist movement. “His entry gave the struggle a great boost, and also changed its name; what was till then the ‘Bihar movement’ now became the ‘JP movement’,” writes Guha. He motivated students to boycott classes and work towards raising the collective consciousness of the society. There were a large number of clashes with the police, courts, and offices, schools and colleges were being shut down.

In June 1974, JP led a large procession through the streets of Patna which culminated in a call for ‘total revolution’. He urged the dissenters to put pressure on the existing legislators to resign, so as to be able to pull down the Congress government. Further, JP toured across large sections of North India, drawing students, traders and sections of the intelligentsia towards his movement. Opposition parties who were crushed in 1971, saw in JP a popular leader best suited to stand up against Gandhi. JP too realised the necessity of the organisational capacity of these parties in order to be able to face Gandhi effectively.

Gandhi denounced the JP movement as being extra-parliamentary and challenged him to face her in the general elections of March 1976. While JP accepted the challenge and formed the National Coordination Committee for the purpose, Gandhi soon imposed the Emergency.

The railways’ protest

Even as Bihar was burning in agitations, the country was paralysed by a railways strike led by socialist leader George Fernandes. Lasting for three weeks, in May 1974, the strike resulted in the halt of the movement of goods and people. Guha, in his book, notes that as many as a million railwaymen participated in the movement. “There were militant demonstrations in many towns and cities- in several places, the army was called out to maintain the peace,” he writes. Gandhi’s government came down heavily on the protesters. Thousands of employees were arrested and their families were driven out of their quarters.

The Raj Narain verdict

While opposition parties, trade unions, students and parts of the intelligentsia had occupied the streets in protest against Indira Gandhi’s government, a new threat emerged before her in the form of a petition filed in the Allahabad High Court by socialist leader Raj Narain who had lost out to Gandhi in Raebareli parliamentary elections of 1971. The petition accused the prime minister of having won the elections through corrupt practices. It alleged that she spent more money than was allowed and further that her campaign was carried out by government officials.

On March 19, 1975, Gandhi became the first Indian prime minister to testify in court. On June 12, 1975, Justice Sinha read out the judgment in the Allahabad High Court declaring Gandhi’s election to Parliament as null and void, but she was given a span of 20 days to appeal to the Supreme Court.

On June 24, the Supreme Court put a conditional stay on the High Court order: Gandhi could attend Parliament, but would not be allowed to vote unless the court pronounced on her appeal. The judgments gave the impetus to the JP movement, convincing them of their demand for the resignation of the prime minister. Further, by now even senior members of the Congress party were of the opinion that her resignation would be favourable to the party. However, Gandhi firmly held on to the prime ministerial position with the conviction that she alone could lead the country in the state that it was in.

A day after the Supreme Court judgment, an ordinance was drafted declaring a state of internal emergency and the President signed on it immediately. In her letter to the President requesting the declaration of Emergency, Gandhi wrote, “Information has reached us that indicate imminent danger to the security of India.” In an interview with journalist Jonathan Dimbleby in 1978, when Gandhi was asked the precise nature of the danger to Indian security that drove her to declare a state of emergency, she promptly replied, “it was obvious, isn’t it? The whole subcontinent had been destabilised.”

For all the latest Research News, download Indian Express App

© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd

The goal of the 21-month-long Emergency in the country was to control “internal disturbance”, for which the constitutional rights were suspended and freedom of speech and the press withdrawn. (Express archive photo)

The goal of the 21-month-long Emergency in the country was to control “internal disturbance”, for which the constitutional rights were suspended and freedom of speech and the press withdrawn. (Express archive photo) The Bihar movement was headed by 71-year-old freedom fighter Jayaprakash Narayan, popularly called JP. (Express archive photo)

The Bihar movement was headed by 71-year-old freedom fighter Jayaprakash Narayan, popularly called JP. (Express archive photo) On June 12, 1975, Justice Sinha read out the judgment in the Allahabad High Court declaring Gandhi’s election to Parliament as null and void. (Express archive photo)

On June 12, 1975, Justice Sinha read out the judgment in the Allahabad High Court declaring Gandhi’s election to Parliament as null and void. (Express archive photo)

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario