From plate to plough: Not all milk and honey

Only 21 per cent of India’s milk production gets processed through the organised sector and the rest passes through unorganised small players. And that’s where the crisis is most intense.

C R Sasikumar

Farmers, who had high expectations from the Narendra Modi government, are a disillusioned lot today. Market prices of several crops have remained well below their minimum support prices (MSPs). Moreover, milk prices have fallen by 20 per cent to 30 per cent (by Rs 5 to10 per litre for cow milk) in several milk-surplus states in western and northern India, including Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan Punjab, Haryana and UP. No wonder, farmers were seen spilling milk on roads or distributing free milk to the poor during their 10-day agitation.

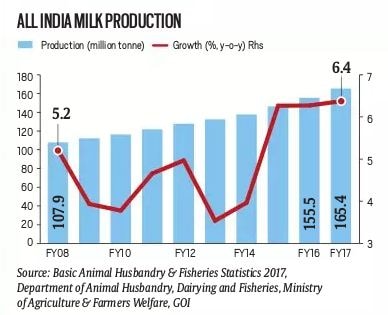

This reminds us of the history of Kheda district in Gujarat, which was struck by a milk crisis in 1946. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel stepped in to solve the problem of low milk prices. He gave India its first and largest milk cooperative (AMUL), and in the process, emerged as a leader of farmers. A similar situation confronts Prime Minister Narendra Modi today. If he can find a solution to the falling milk prices, he will emerge as an undisputed leader of farmers. India is the largest producer of milk (165.4 MMT in 2016-17); the value of milk is more than that of rice and wheat combined. So, it is India’s biggest agri-produce. It is a source of income to small and landless agri-households — 70 per cent of those earning their livelihood from milk are women.

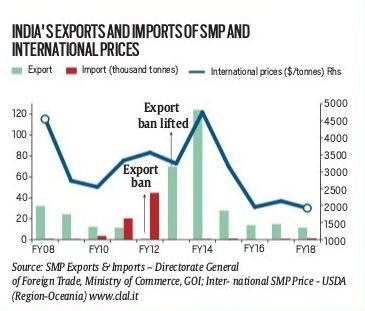

But before we get to the plausible solutions to the problem of falling milk prices in India, let us try to understand what led to this situation. First, the increase in milk production since 2014-2015 has been unprecedented (6.3 per cent per annum between fiscal year FY 2015 and FY 2017; FY 2018 figures are not yet finalised), compared to about 4.2 per cent in the three years preceding that (see graph-1). Moreover, the milk output, instead of falling during the lean (summer) season, registered high growth in 2017-18 vis-à-vis 2016-17. Doubts that some experts raise about the authenticity of milk production data, the fact that the prices are falling indicates that supplies exceed demand. Second, in such a situation of glut, India should have been exporting large quantities of skimmed milk powder (SMP). Unfortunately, the global SMP prices have tumbled $4,744/tonne in 2013-14 to $1,925/tonne in 2017-18, making SMP exports unviable. India’s SMP exports plummeted from an all-time high of 124 thousand tonnes in 2013-14 to just 11.3 thousand tonnes in 2017-18 (see graph-2). Not finding a good export outlet has accentuated the milk price crisis in the country.

Third, market information today suggests that some large cooperatives (like AMUL) or even some large organised private players with a lot of value-added milk products — and with contracts with farmers — have been able to hold the price line for farmers. But innumerable small players dabbling in liquid milk and/or SMP have led to a substantial reduction in procurement prices. Remember, only 21 per cent of India’s milk production gets processed through the organised sector and the rest passes through unorganised small players. And that’s where the crisis is most intense.

What can PM Modi do to tide over the milk price problem for millions of small farmers? Here are a few suggestions. One, create a buffer stock of two lakh tonnes of SMP through NDDB. This would imply withdrawing two million tonnes of liquid milk from the market, improving the market sentiment and upping the price line. At the current market price of about Rs 150/kg, it will cost about Rs 3,000 crore, much less than the package that was recently offered to the sugar industry.

What can PM Modi do to tide over the milk price problem for millions of small farmers? Here are a few suggestions. One, create a buffer stock of two lakh tonnes of SMP through NDDB. This would imply withdrawing two million tonnes of liquid milk from the market, improving the market sentiment and upping the price line. At the current market price of about Rs 150/kg, it will cost about Rs 3,000 crore, much less than the package that was recently offered to the sugar industry.

Two, introduce SMP to the futures market platform. The global prices of SMP are not likely to remain depressed for long. This is because at current prices even the most efficient New Zealand milk farmers are making losses. As global SMP prices improve, NDDB can sell these stocks at a profit.

Three, bring SMP under the Merchandise Exports Incentive Scheme (MEIS). Today, butter and ghee are in that category, but not SMP. This anomaly must go. The scheme could be used to incentivise farmers who have to make do with poor back-end infrastructure for collection and marketing of milk. This would help to ramp up organised structures through cooperatives and encourage the large private players in the industry. The scheme would be WTO compatible. Four, incentivise investments in value-added products in the organised sector — this could include curd, buttermilk, cheese, ice-cream and even chocolates. Improving the production of more value added products can help farmers stabilise their milk prices.

Five, expand domestic demand for higher milk consumption through concerted campaigns, especially in the 115 aspirational districts where malnutrition is high. In fact, in these districts, the government could introduce milk in mid-day meal schemes. Use the SMP buffer to supply large quantities to the armed forces, hospitals and other large institutional players.

The bottom line is that India has to work on two fronts simultaneously: One, create demand to match rapidly increasing supplies of milk; Two, ensure that its dairy sector develops on globally competitive lines. In order to cut down costs of milk production, India needs to increase the productivity of its milch animals, which is far below (indigenous cows 2.8 litres, crossbreds 7.5 litres, and buffaloes 5.2 litres per day) the global standards of 20 litres plus/day. Cross-breeding with high-productivity animals of foreign breeds and pure indigenous breeds, with sex selection semen technologies assuring female progenies, is the way forward. The technologies exist, but the country needs to ramp its R&D and agriculture extension department to transform this sector into a vibrant, competitive and more remunerative sector for farmers.

Will PM Modi seize this moment? If he does, it will make good economics for farmers and good politics for him.

Gulati is Infosys Chair Profesor for Agriculture and Juneja is research assistant at ICRIER

Gulati is Infosys Chair Profesor for Agriculture and Juneja is research assistant at ICRIER

Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture and Juneja is research assistant at ICRIER.

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

More From Ashok Gulati

- From Plate to Plough: Why farmers agitateAn efficient and sustainable solution for better prices really lies in ‘getting the markets right’ by overhauling the agri-marketing infrastructure and its associated laws...

- From Plate to Plough: Pieces of a marketA single national agriculture market, promised by the BJP in its 2014 manifesto, remains a pipe dream. Can the government reform the broken APMC structure…

- From Plate to Plough: Premium delayed, farmer deniedPradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana does not inspire confidence of farmers. They have to wait for months, sometimes years to get compensation...

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario