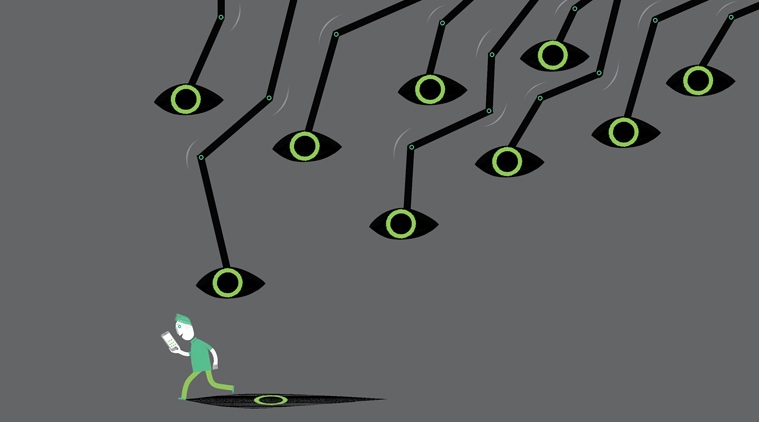

When the state plays I spy

Recent MHA notification authorising surveillance powers for 10 agencies points to asymmetries and loopholes in law and policy on privacy.

A recent Gazette of India notification from the Ministry of Home Affairs, authorising 10 agencies with interception, monitoring, and decryption powers under Section 69 of the Information Technology Act (IT Act), has provoked considerable disquiet. While it might be tempting to portray the angry exchanges across different political parties inside and outside Parliament as partisan posturing, we would be missing the significance of pre-existing — and rapidly growing — privacy and surveillance concerns in India.

Privacy concerns regarding the state, in terms of the exercise of surveillance powers, stems from the asymmetry and monopoly of power in favour of the executive. These concerns have only increased in a digital world where our intimate details, thoughts, and relationships are contained in our smartphones and computers.

The notification, and the underlying section and rules of the IT Act have re-ignited the debate on the constitutionality of such surveillance measures. First, unlike the Telegraph Act, the powers under the IT Act are broader, and include the power to intercept, monitor, and decrypt “any information” generated, transmitted, received, or stored in “any” computer resource (think all your WhatsApp conversations, Facebookmessages on your computer and smartphone). Second, while the amended Section 69 of the IT Act, and its 2009 regulations, empowered the central and state governments, or “any of its authorised officers”, to conduct such activities, the notification has empowered 10 agencies (including the Commissioner of Police, Delhi) to do so. The existing statutory framework indicated a case-by-case basis for invoking such surveillance powers, based on authorisation by the “competent authority”. Orders for such digital surveillance actions could only originate after the pre-approval of the Union home secretary or the appropriate state government’s home secretary; law enforcement agencies had no competence to do so. However, the MHA notification denudes the competent authority of such powers and sets up the stage for mass surveillance.

The actual notification itself does not clearly require the Union Home Secretary to pre-approve such surveillance orders. Though the Union Government has sought to rebut the view that the Home Secretary’s requirement to oversee and pre-approve has been curtailed, government spokespersons have justified the notification stating the need to reduce the burden on the Home Secretary and de-centralise such data access and surveillance actions. In contrast, the legal regime under the older Telegraph Act and its rules still explicitly requires the appropriate home secretary to pre-approve wiretapping orders, except in emergency situations. Third, after the Supreme Court’s decision in the privacy (emphasising the need for necessity and proportionality) and Aadhaar cases (that allowing disclosure of information in the interest of national security in the hands of a joint secretary is unconstitutional and judicial scrutiny may be necessary), these legal provisions are untenable.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario