TERRORISM

The day that Basque terror group ETA lost the support of the street

Civic revolt over July 1997 murder of Miguel Ángel Blanco was a watershed moment in fight against terrorism

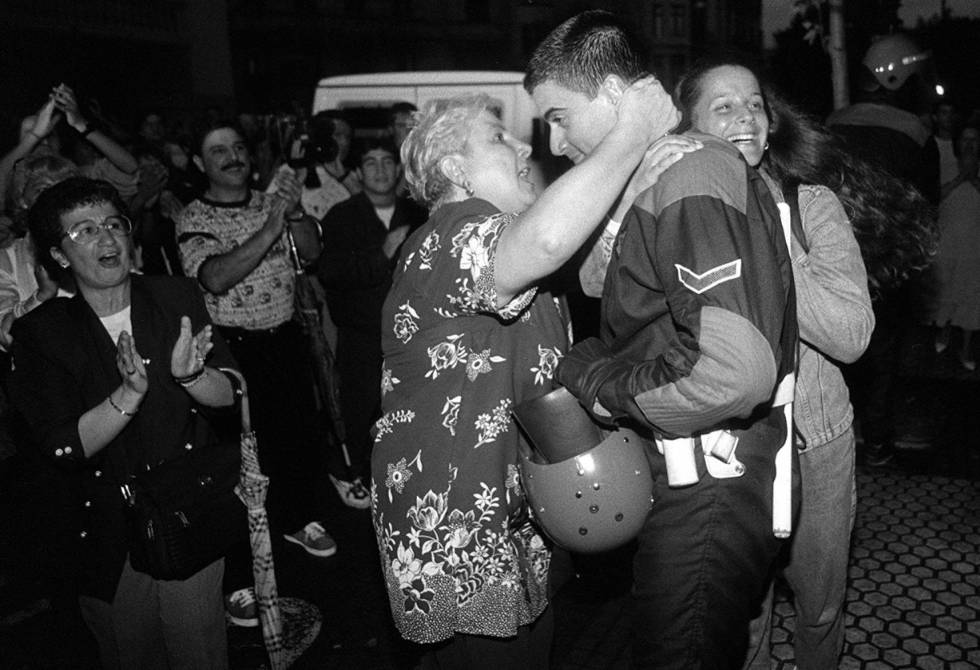

Family members of ETA victim Miguel Ángel Blanco on the balcony of the town hall in Ermua (Vizcaya).

LUIS R. AIZPEOLEAPeriodista de EL PAÍS

San Sebastián

“On the afternoon of July 10, 1997, as I was returning from doing some paperwork in Mondragón, I was told that ETA had kidnapped a young councilor, Miguel Ángel Blanco, from our own town. I told the people around me, ‘ETA is not getting away with this scot-free!’ I immediately called a plenary session and told the municipal police to go out on the streets and announce a street protest for 8pm.”

The speaker is Carlos Totorika, a Socialist who has been the mayor of the Basque town of Ermua since 1991. This is where the 29-year-old Popular Party (PP) councilor was abducted by a terrorist cell at 3.30pm on the platform of the local train station.

Between 1976 and 1994, ETA caused 771 deaths. Between 1995 and 2010, there were 98 killings

It was a massive protest. Thousands of locals packed the streets of Ermua, population 17,000, demanding Blanco’s release. The following night, thousands more held a vigil. Totorika viewed the kidnapping as a challenge issued by ETA, and he believed that Ermua would be up to that challenge.

“I knew there was going to be a powerful response, because people were really sick and tired,” he says in reference to a period of time when ETA activity was at a high. A 2015 report commissioned by the Basque government found that ETA committed most of its violent acts not under Franco, but during the consolidation of democracy. Between 1976 and 1994, ETA caused 771 deaths. Between 1995 and 2010, there were 98 killings.

There had already been significant protests over the murder of law professor and Constitutional Court justice Francisco Tomás y Valiente in February 1996. The same with the abductions of the businessmen Julio Iglesias Zamora and José María Aldaya. And with the kidnapping of prison worker José Antonio Ortega Lara, who was held for 532 days between 1996 and 1997. Spaniards were shocked by images of an emaciated Ortega Lara upon his liberation by the Spanish Civil Guard, who found him inside a humid underground cell so small that he could only take three steps in it.

“One day, the streets were plastered with posters showing local residents’ faces in the middle of a target,” recalls the mayor, alluding to a classic intimidation technique used by ETA supporters in many Basque towns. “I called a plenary session inside a local movie theater to get people to participate. We put the [pro-ETA party] Batasuna councilors on the defensive. In Ermua, respect for life and human rights took precedence over ethnic patriotism. There was a plurality of thought.”

In the meantime, regional Basque premier José Antonio Ardanza, who served between 1985 and 1999, was calling all the signatories to the Ajuria Enea Pact, a cross-party effort to fight terrorism in the region through coordinated work and international cooperation. José Luis Zubizarreta, who was Ardanza’s advisor at the time, remembers that ETA was making it a condition for Blanco’s release that all its prisoners serving sentences across the Spanish geography had to be transferred to Basque penitentiaries within the next 48 hours.

“The Ajuria Enea Pact replied that Blanco should be released because those conditions were impossible to meet, and it called a street demonstration in Bilbao for Saturday at noon, a few hours before the deadline,” he recalls.

Following the civic rebellion in the Basque Country, political leaders showed that they were not up to the task

The Basque premier traveled to Ermua to show his support for the Blanco family. “We let the family use municipal facilities so they could talk to people there,” says Totorika, the mayor. “They had enormous support. A network was set up to deal with all the visitors who came to Ermua. There was a lot of solidarity on display.”

The Bilbao march of July 12 was the largest anti-ETA protest in Spanish history. “A lot of people showed up who had never been to this kind of demonstration before, and they came to help save Miguel Ángel, a young man from a working-class family with whom they could identify. The media covered those emotional 48 hours, and people felt like they were in the spotlight,” says José María Calleja, an activist who was involved in the social movements of that period.

So when a mortally wounded Blanco was found two hours later in the nearby town of Lasarte, there was an outpouring of indignation. The mayor of Ermua broke the news from the balcony of the town hall, where he stood along with members of the Blanco family. Thousands of people began chanting: “Murderers! Murderers!” A group of people set fire to Batasuna’s party headquarters, and Totorika helped put it out, fire extinguisher in hand.

“There were quite a few people who thought that, after all the demonstrations, ETA would release him; but they saw [ETA’s] infinite cruelty, and indignation was stronger than fear. A lot of people protested in front of Batasuna headquarters, and special ops officers from the regional police force, the Ertzaintza, took off the balaclavas they routinely used to conceal their identities as a safety measure against an ETA attack. In Ermua, many women kneeled and yelled out: ‘ETA, here is the back of my neck!’,” recalls Calleja.

“The democratic uprising of the Basques against ETA caught on in the rest of Spain, and a slogan was born: ‘Yes to Basques, No to ETA’,” he adds about that watershed moment in Basque and Spanish history. There was a proliferation of demonstrations across Spain to support Basque society’s rebellion against the terrorists.

Batasuna definitively lost its hold on the street because people shook off their fear

CARLOS TOTORIKA, MAYOR OF ERMUA

“ETA lost the arm wrestle,” confirms Totorika. “Terrorism tries to create fear and paralyze people with it. But indignation was greater than fear. People felt safe when they saw that they were united and could count on support from the institutions.”

“After Ermua, Batasuna people found themselves on the defensive, and some of them looked down when they saw us on the street,” adds Calleja, underlining a notable change in attitude by pro-ETA individuals who had, until then, felt that they “owned the streets.”

The civic revolt had another kind of impact on Batasuna. In an unprecedented move for the radical political group, one of its leaders, Patxi Zabaleta, condemned the murder and later headed a breakaway party named Aralar. Even former ETA leaders serving prison sentences, such as Joseba Urrusolo and José Luis Álvarez, aka Txelis, issued condemnations.

The Spanish interior minister at the time, Jaime Mayor Oreja, stated that “Ermua is to ETA what the Burgos process was to Francoism: the herald of its de-legitimization,” alluding to a summary trial held in 1970 against 16 ETA members.

Yet following the civic rebellion in the Basque Country, political leaders showed that they were not up to the task. The cross-party unity was broken. Spanish Prime Minister José María Aznar tried to capitalize on the wave of anti-terrorist sentiment, and Xabier Arzalluz, the head of the moderate Basque Nationalist Party (PNV), signed a deal with Batasuna that came to be known as the Lizarra Pact. Progress was set back by several years.

Even so, the social momentum gave birth to civic groups such as Foro de Ermua and Basta Ya, and pushed legislators to pass the Solidarity with Victims of Terrorism Act of 1999 and the Political Party Act of 2003, which outlawed parties that openly supported acts of terrorism.

After the civic rebellion at Ermua, victims began to take center stage and Batasuna definitively lost its hold on the street

Ardanza, the former regional premier, admits that “Ermua represented a before and after in Basque society.” Totorika and Calleja confirm that: “In the 1990s, the street demonstrations with people wearing blue lapel bows began to award public visibility to ETA’s victims, and to challenge ETA’s control over the streets. After the civic rebellion at Ermua, victims began to take center stage and Batasuna definitively lost its hold on the street, because people shook off their fear. Every murder after that came up against mass protests, and we began thinking that we could defeat ETA, which took a downhill path without any brakes.”

ETA would still go on to murder 67 more people before ceasing its violent activities 15 years later. Two of their targets were leading members of this civic rebellion: José Luis López de Lacalle and Joseba Pagazaurtundua. But ETA was eventually defeated, and there is no doubt that the citizen revolt that began in Ermua was one of the determining factors in that outcome.

English version by Susana Urra.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario