Govt’s scheme to pay Rs 6,000 to poor rural households will up their expenditure, reduce poverty

The annual benefit of Rs 6,000 will provide the household some cushion against unexpected expenditure due to illness or accidents, which pushes many people to the margins of the poverty line — at times, even below it.

In the last week of February, the government launched a scheme to pay Rs 6,000 every year to poor rural households who own less than 2 hectares of land. The scheme will have an annual outlay of Rs 75,000 crore. The beneficiaries received the first installment of Rs 2,000 on February 24. Congress President Rahul Gandhi has mocked the scheme saying that Rs 6,000 per year translates to Rs 16.43 per day per family, that is a pittance and not much of a help to the poor. To one with declared assets around Rs 9 crore and an annual income exceeding Rs 92 lakh, Rs 16.43 per day will appear to be peanuts. I examine here what this amount can mean to the poor in India.

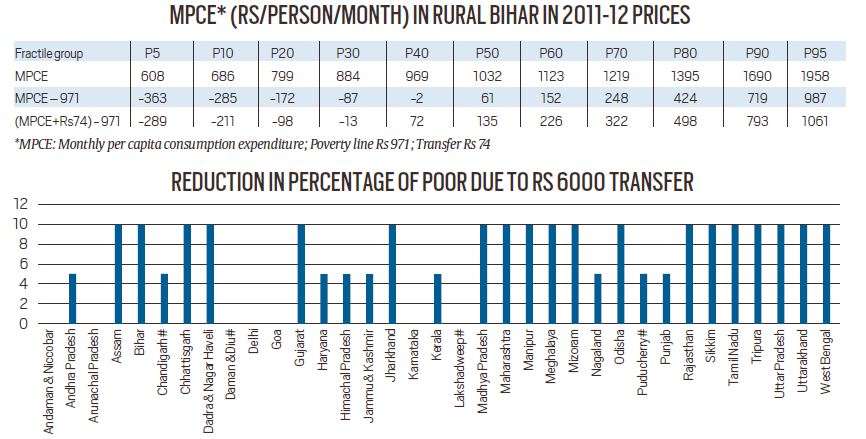

To explore the scheme’s impact on the poor, I looked at the monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) of households belonging to different fractile groups in states of India. The national sample survey (NSS) of household expenditures for 2011-12 (the latest publicly available) provides MPCE by fractile groups such as the poorest 5 per cent, the next 5 per cent, the next 10 per cent, and so on. If we add the monthly per capita value of the Rs 6,000 transfer to each class’s MPCE, we obtain the addition to its MPCE. However, the transfer in 2019 has to be converted to the equivalent transfer in 2011-12 by adjusting for inflation in the state’s consumer price index. The modified MPCE can be compared with the poverty line in the state. We can then assess how many people will cross the poverty line with this transfer of Rs 6,000 per family per year.

I illustrate the procedure with the example of Bihar. In 2011-12, the household size in rural areas in the state was 5.5. The consumer price index for rural areas changed from 111 in 2011-12 to 137 in 2017-18, giving a ratio of 1.23. Therefore, Rs 6,000 per family in terms of 2011-12 prices translates to Rs 74 per month (Rs 6,000/12/5.5/1.23). According to the Rangarajan Committee Report, the poverty line for rural Bihar was Rs 971 in 2011-12. The table shows the impact of the transfer on different different fractile groups, assuming all get the money — though about 70 per cent of the rural households are likely to be eligible in Bihar.

Before the transfer, 40 per cent of people’s expenditure in Bihar was below the poverty line. After the transfer, only 30 per cent of people in the state remained below the poverty line. It should also be noted that the gap between the poverty line and the expenditure of those who remain poor was reduced. Thus, the transfer leads to significant reduction in poverty. A similar calculation for all the states and union territories show a 10 per cent reduction in the percentage of the poor in many of them. (See figure)

The actual reductions are likely to be greater once one accounts for the benefits of the food security scheme introduced by the UPA government. Under this scheme, a poor household gets 35 kg of rice, wheat or coarse grains every month — rice at Rs 3/kg, wheat at Rs2/kg and coarse grains at Rs1/kg. This scheme was introduced in 2013-14, so this should reduce the poverty line over the Rangarajan estimates for 2011-12.

The financial value of who benefited from this Food Security Act can be roughly assessed as follows. The NSSO survey of consumption expenditure of 2011-12 provides data on the quantity of rice and wheat obtained from the ration shop and market as well as the prices at which they were obtained. The average purchase by the bottom 5 percentile households in 2011-12 was 15 kg of rice and 6.5 kg from the PDS shops at around Rs 3.5 per kg of rice and Rs 3.7 per kg of wheat. They also purchased from the market 20 kg of rice at Rs 15/kg and 13 kg of wheat at Rs 11/kg.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario