Published: March 10, 2019 1:43:12 am

Gained in Translation: Guru and me

The writer is a celebrated Malayalam short-story writer. ‘Guru’ is the late seer and scholar Nitya Chaitanya Yati.

Written by Ashita

There was a time, 35 to 40 years ago, when there was an unspoken consensus in society that a woman who had not gotten married by the age of 30 would stay a spinster all her life. I doubt if this perception has changed even today. A woman aged over 30 is considered a decaying vegetable, unattractive like the dry desert, a burden that no intelligent young man would want to bear.

After an overprotected childhood and a stormy youth, I had remained unmarried at 27. My younger sister had got married at an age which was deemed appropriate. All this was a topic of discussion in the neighbourhood. People were discussing that I may not be a woman, or perhaps that I was a transgender, and that a moustache may be growing above my upper lip.

I had been forced to take a degree in English literature, though my preference was Economics, because it was thought that girls with a degree in English were preferred for marriage by the uneducated boys working in the Gulf. Marriage proposals from people as varied as a Class VIII dropout who had joined the Army to Class X-pass stenographers came for me, a postgraduate and university topper. There were some relatives who advised me to join an ashram and resolve the conundrum!

Though it was easy to run away to the ashram, I did not have any spiritual inclination. If there was a god, he was there somewhere. I never felt he had any interest in me. Nor I in him. It was a time I believed that Marxism was the loftiest dream humanity had seen. I was a committed atheist.

At that time, at 27, I got married. A year later, a child was born to me. By 32, Guru arrived in my life. There was a particular reason for it. The daughter of a distant relative had committed suicide at 19. I had struggled to console the parents, who were distraught, and was wondering who to turn to for advice.

I thought of all the literary figures. None of them, I felt, had the self-awareness to handle this. Then, one day, I saw my daughter kiss the photograph of a bearded man on the open pages of Mathrubhumi Weekly.

Smiling, I asked her: “Who is it baby?”. She answered: “Swami”.

Curious, I took the magazine. I didn’t think he was much of a sanyasi. The article was about home. I started reading it and got hooked. Not bad, this sansyasi, I thought. He had opened the doors to a vast area of knowledge of which I, who ran a household, was unaware. I decided I would ask him about my predicament. The editor of Grihalakshmi (a Malayalam women’s magazine), P B Lalkar, got me his address. That’s when I became aware that he was a sanyasi and was staying at an ashram in Ooty.

Lalkar assured me that he would reply if I wrote. But a grave fear enveloped me. I feared that my life would never be the same hereafter and thought someone was pushing me down a cliff. I strained for about four to five days and wrote to him, telling him I faced no problems in life, and in a suitably vague tone asked if Guru did respond to such persons. I got a response in clear, legible handwriting. What was surprising is that I recognised that it was not Guru’s handwriting. So I wrote back: “Received your letter. It felt as if someone has extended a rose to me after taking away its smell. When Guru writes to me, I want it to be in your handwriting.”

I received a reply even for that. That’s when I realised that Guru was in his 60s and dictated his responses to children in his ashram. I sought his advice on my relative’s concern. If their daughter died at 19, tell them to conduct the wedding of 19 girls, was his advice. There was no tinge of sympathy in his reply. What a stone-hearted man, I thought.

I squabbled with him for nearly a month, telling him we are ordinary people and that we feel distraught when someone dear to us dies. His response was that it was stupid to grieve for more than a month when someone dies. What I remember is that I didn’t write to him thereafter.

Then, one day, I received a letter, the gist of which was that he was visiting Thiruvananthapuram for a lecture and would visit me. I panicked. After a time of youth, when I sowed the wind to reap a whirlwind, I was living within the happy confines of marriage with a little pearl. I did not want anyone to breach that space. Besides, I had no idea how to talk to a sanyasi. And, he was the head of a gurukul. He will come accompanied by cars, with many disciples and admirers — how shall I receive them? This left me confused.

So I immediately wrote back. “You don’t have to come. It is not important to meet me. If you still wish, please do not come accompanied by many cars or admirers. I don’t like all that,” I wrote in my letter.

He replied. “I am old. So, I need at least one person to help me.” Peter Oppenheimer accompanied him.

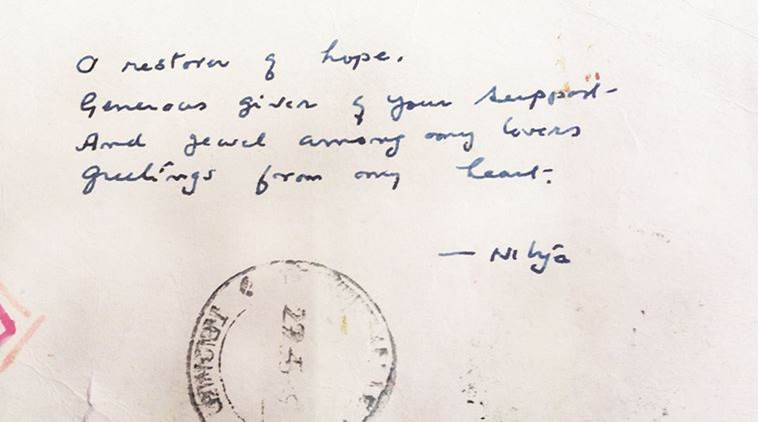

Not knowing what to tell him, I stayed mum. He had a glass of water and bid me goodbye. After returning to Ooty, a letter came in my address. This is that letter:

“O restorer of hope; Generous giver of your support — And jewel among my lovers; Greetings from my heart” — Nitya.

On reading it, I felt it was a letter to Muni Narayana Prasad (a sanyasi disciple of Guru). I felt that he, in his old age, had got the address wrong and posted it to me instead. Surprisingly, the greetings he sent me in the letter he wrote with his own hand just before his samadhi were the same — except that the letters were a little wobbly.

Translated by Amrith Lal

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario