BCCI seems to have forgotten that foreign policy is not its mandate

There was a time when cricket administrators from India and Pakistan worked together to democratise the game.

It was at Lord’s over biryani — what else could have India and Pakistan bonded over — where cricket’s big Asian coup was planned. A day after the 66-1 underdogs India won the 1983 World Cup, the Indian cricket board president, N K P Salve, and his Pakistan counterpart, retired Air Chief Marshal Nur Khan, met for lunch at the home of cricket. Salve was pleased but a shade sad too. He still couldn’t get over the snub he got from those veto-power wielding snooty MCC boys over his request for extra tickets for the India-West Indies final. Later, he would write in his book that it wasn’t the refusal but the rude rebuff that had hurt him.

Salve would share his pain with Khan, who, too, reserved special scorn for the ICC’s undemocratic ways. With utter disbelief and disdain, the two would contrast Lord’s alleged ungraciousness to the Subcontinent’s legendary hospitality. “Extra tickets?… that’s the least we would do for guests,” they would lament. History books say that it was Khan’s very pragmatic query to Salve that would eventually trigger cricket’s eastward shift. “Why can’t we play the next World Cup in our countries?” he had asked. Next year, in 1984, the India-Pakistan-Sri Lanka consortium would join forces to drag the World Cup out of England, and ferry it all the way to Asia.

Salve and Khan — unlikely allies from either side of the prickly fence — had done the impossible. They didn’t let their day job come in the way of their honorary pursuit to promote the game they were so passionate about. One was a life-long Congressman, an Indira Gandhi loyalist, a sitting Lok Sabha MP when India-Pakistan went to war in 1971. The other, Pakistan Air Force’s commander-in-chief during the 1965 war against India. But on that monumental June afternoon at Lord’s, the bitter neighbours decided that they would watch each other’s back at ICC meetings.

Salve and Khan crystalised cricket’s parallel power centre and called it the Asian bloc. In years to come, the two nations would jointly host two World Cups. In Jagmohan Dalmiya, a businessman from Kolkata, and Ehsan Mani, a Rawalpindi-born British-educated chartered accountant, the ICC got its most influential chiefs responsible for filling cricket’s so-far empty coffers. Mani and Dalmiya would also collaborate to teach the cricketing world the economics of TV rights.

With time, India and Pakistan would have differences. At the turn of the century, Pakistan’s dip coincided with India’s phenomenal rise. The world stopped touring Pakistan after the 2009 terror strike and the IPL franchise shunned Pak players on auction day. The BCCI would diligently follow the Indian government’s policy to avoid Pakistan in bilateral series but in private, the cricket officials would day-dream about past Indo-Pak games. The buzz before those games, those VVIPs queuing outside the cricket centre, phone calls from offices as high as the PMO for passes… Oh how much they missed those days of a windfall when cricket triggered a virtual curfew in India and Pakistan! For both emotional and economic reasons, they longed for cricket’s biggest tamasha but they were willing to wait.

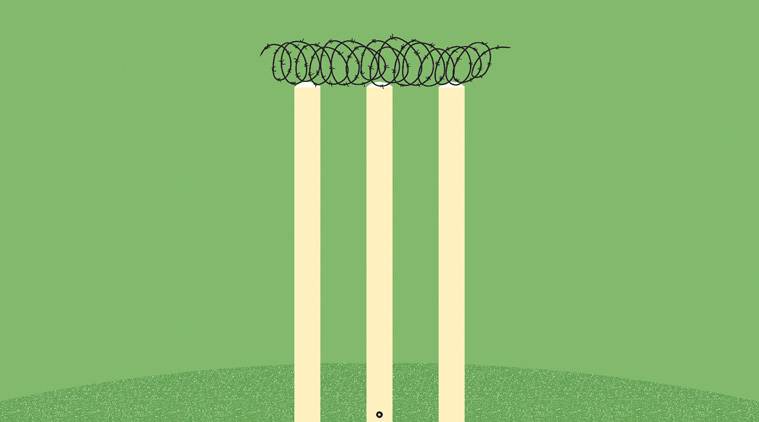

A fortnight ago, in the wake of the Pulwama terror attack, the BCCI did something unprecedented. They asked the ICC to ban Pakistan. The (CoA) chairman, Vinod Rai, said Pakistan, like South Africa in the past, should face cricket apartheid. It was an ugly, ill-advised wild cross-batted heave played with closed eyes and from way outside the crease. It was a misadventure that didn’t follow any textbook. It certainly wasn’t inspired by the Olympic charter that asked administrators to remain apolitical in all circumstances. The fundamental principle of Olympism calls the practice of sport a human right. It discourages discrimination and promotes “friendship, solidarity and fair play”. If those standards were too high and idealistic, even turning the pages of Indian cricket history would take them to the chapter of solidarity that Salve and Khan had so meticulously written.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario