Boys And Their Bathrobes

#MeToo India has squashed clichés once linked with victims of sexual harassment.

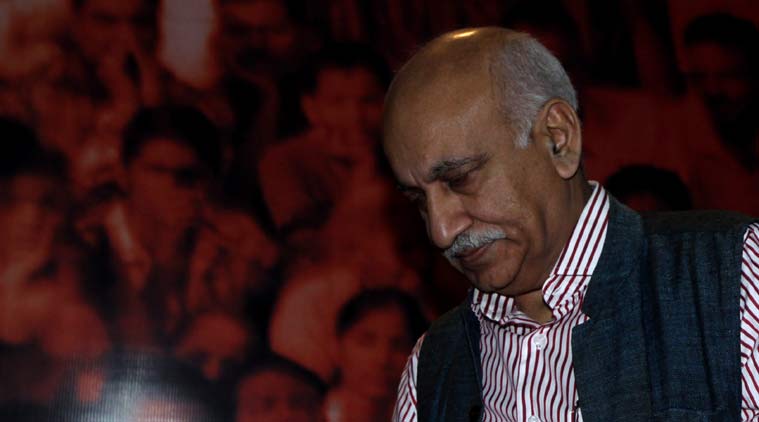

Several women, mostly journalists, claimed they were sexually harassed by M J Akbar during his stint as an editor.

Besides bombing fear from the minds of “victims” of sexual harassment by flagging the road not taken, #MeToo India has also bled out the clichés of appearance that shrouded women who spoke up. Some will argue this is too trivial a matter to table when a posse of women journalists with strength of head and heart declared war over BJP minister M J Akbar, a powerful former editor. When a less known actor like Tanushree Dutta stuck to her ground against an established actor like Nana Patekar. When women from different professions are shedding masks of shame that have been pasted on them for years to call their predators. Why bring up trivial gendered judgements?

Because trivialised is exactly how generations of women felt when the length of their dresses, the depth of their necklines, the sharpness of their tone, the boldness of their career choices, the colours of their lipsticks, their ways of being and realising their lives were blamed for what befell them. For decades, the dominant discourse around sexual harassment remained around “the type of woman she was” or “the way she spoke”, or how she would “smoke and drink” or “how she dressed for work”. A venomous litany of judgments that would force women of all classes, backgrounds and cities to wonder if they had somehow contributed to their indignity.

But #MeToo India has washed away those demeaning caricatures of injustice. So persuasive, so pertinent, so direct and unambiguous is the manner used by the journalists who have accused Akbar of sexual harassment — with descriptions of where he called them, drinks that he allegedly asked them to make for him, where all he touched them violating their bodies and self-respect, how his breath smelt, that it has driven shame from the side of the victim to that of the perpetrator.

The unapologetic directness of these ladies, the authenticity that can only come from truthful narrations, has, in fact, stripped away the embarrassment that clouded us in the past when we attempted to use words like “he touched my breasts”. Vocabulary is shaped by our thoughts but once vocalised, it shapes our thoughts. One of the big lessons from #MeToo India is that truth doesn’t need couching in “respectable language”.

I worked at The Asian Age under Akbar in 1995-1996 for less than a year as part of the Sunday magazine. I was never Akbar’s victim but enough talk about his “ways with women” spun around the office every day. That newsroom was a complicated place to function in because it quaked with gender politics. Two days back, one of my ex-Asian Age colleagues recalled a sick joke that went around then: If Akbar didn’t make a pass at you, it meant you were unattractive. That’s what I mean by the politics of appearance and how fraught and damaging it can get.

Now when I read the disturbing experiences of my ex-colleagues as well as of Priya Ramani, my editor at Mint Lounge, a wave of distress envelopes me. I find myself a lesser woman. Was I witness to sexually improper behaviour but went around my job mutely? Did I even bother to understand what I labelled as toxicity? I was not in harm’s way, did that absolve me of the duty to stand up? How did we define sexual harassment in those days? No idea.

Later in my other jobs, where I worked with some extraordinary men and women, there were always some (mostly men but a few women too), who would taunt the well-turned-out about how we took so much trouble with our exercise and makeup to keep ourselves in the “good books” of the bosses. “Luxury and a sari-clad woman? Don’t be ridiculous, get me a lady in a sexy gown to anchor the event, then let’s talk about luxury,” said one. Male. “Why don’t you wear chiffon saris to show off your figure, you will get a better raise, textiles make you look plump.” Female.

Here’s what I want to say to all those who have blamed women’s short dresses, painted lips, blow-dried hair, fitted shirts or chiffon saris. Boss, the garment that will be remembered in #MeToo India (and worldwide) is not a dress or a blouse. It’s the bathrobe. Worn by men, from Harvey Weinstein to Dominique Strauss-Kahn to M J Akbar.

The writer is the editor of The Voice of Fashion

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

More From Shefalee Vasudev

- Sari, they’re so wrongAll the same, when you study the statements this article stands upon, it is a great example of poorly researched, unfair journalism that uses unverified…

- This sari momentThe garment is like fashion itself — a little ahead of all that’s done about it..

- Alt+FashionSwitch to Bungalow 8 in Mumbai and though it may be large and contemporary,there’s a similar sense of independence and freedom from the tried and…

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario