| MercatorNet | March 24, 2017

Polyphony? Or cacophany? Prelude to a reformation in church music

‘Bleating’, ‘howling’ and ‘whinnying’: Renaissance critics on church choirs.

Image: Ferdinand Van Kessel, Cat's Concert, c. 1696 (cropped) via Wkigallery.org.

Not for commercial use.

Not for commercial use.

In the preceding articles on the topic of music and the Reformations of the sixteenth century, I have tried to frame the socio-cultural and musical context of the Reformations. In this article I will discuss viewpoints on church music found in many treatises and writings of the era.

In spite of the extraordinary blossoming of Renaissance sacred music, approval of church polyphony was far from universal. Many churchmen complained of the waste and time and money which professional church music seemed to imply. For example, Agrippa von Nettesheim claimed that “even the divine offices themselves and the sacred prayers and petitions are performed by lascivious musicians hired at great price,” while a Spanish Dominican friar, Martin de Azpilcueta, maintained that money should not be spent on singers “who know no Latin” and are “frivolous, dissolute and foolish”.

Indeed, Philip Stubbes, an English author, reported the opinion held by many of his contemporaries, who were, it seems, unimpressed by music in general. For them, in Stubbes’ words,

“[Music] hath a certain kind of smooth sweetness in it, alluring ye auditory to effeminacy […], [which] at first delighteth the ears, but afterwards corrupteth and depraveth the mind, making it queasy and inclined to all licentiousness of life whatsoever […]. If you would have your son soft, womanish, unclean, smothe mouthed, affected to bawdry, scurrility, filthy Rimes & unseemly talking: briefly, if you would have him, as it were transnatured into a Woman, or worse […] set him […] to learn Musicke, and then you shall not fail your purpose”.

Stubbes’ tirade is really amusing for contemporary readers, but it mirrors the prejudice about music which some sectors of sixteenth-century society still maintained.

On other occasions, it was the low quality of music that was harshly criticised: in other words, church music was not the nefarious activity Stubbes portrayed, but simply not up to the appropriate standard..

Several contemporaneous writers attributed particular features to the singing styles of the different countries. Typically, according to Hermann Finck, “the Germans bellow, the Italians bleat, the Spaniards wail, the French sing”. Ornitoparchus maintained that “the English iubilant, the French [Galli] sing; the Spaniards display crying; as for Italy, those who inhabit the Genovese shores are said to caprisare [to jump like goats], the others bark; as for the Germans, although it shames to say so, they really howl like wolves.” Though the French should be proud of being the only ones apparently able to “sing”, there may be a hidden (and not-so-flattering) wordplay here: Galli means “roosters” as well as Gauls, so their singing could have been somewhat raucous in turn.

While such sentences make rather funny reading, the realities they point to were a true source of worry for those writing them. In their eyes, humans had a God-given nature higher than that of animals and beasts; so, when a church choir sang so badly that the aural result appeared similar to animal noises, this implied a serious loss for human nature itself. As Jacopo Sadoleto wrote, humans singing with animal voices put themselves on a par with beasts, and were de-spiritualising their very soul. We can interpret in the same way the words of Agrippa von Nettesheim describing a choir which sang “not with human voices but with the cries of beasts: boys whinny the discant, some bellow the tenor, others bark the counterpoint, others moo the alto, others gnash the bass”.

Still others complained that church singers did not care about the volume of their singing, and particularly they did not adapt it to the level of their neighbours. Hermann Finck sarcastically wrote: “the singers [suffer] from the delusion that shouting is the same thing as singing. The basses make a rumbling noise like a hornet trapped in a boot, or else expel their breath like a solar eruption.”

Here too there was a theological concern behind the colourful description: when church singers did not listen to their neighbours, this became an aural symbol for the absence of communion in the community of believers. Since singing together should express the congregation’s unity, and since this unity can only be achieved through reciprocal listening, the lack of interest in the overall result is a powerful and negative icon of disunity and rivalry.

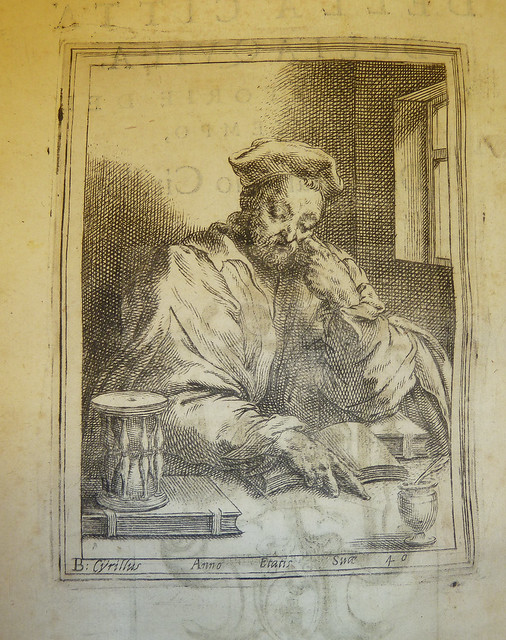

In fact, some of the preceding critiques were summarised by yet another churchman, the Italian Bernardino Cirillo (pictured left), in a long and often-quoted letter on polyphony and the role of church music. While he did not eschew the usual zoological images (he spoke of “a January of cats and a May of bulls”, alluding in fact to braying donkeys), his points were more profound and nuanced.

For him, the Church ought to conform her music to the holiness of the mysteries she celebrates; therefore, not all kinds of music were equally well-suited for the divine praises. He argued that Michelangelo’s frescos in the Sistine Chapel were magnificent, and true masterpieces showing the human power over nature; nevertheless, he thought that they were rather a display of the artist’s virtuosity than a true example of “sacred” art in the service of prayer.

Similarly, said Cirillo, church music should inspire heartfelt devotion and piety, but it had an even higher task: it should represent the Church’s interior renewal and its pastoral role for humankind. He hoped that “our Church, with its deeds, moves [people] to religion and piety”, and that she would set an example for all believers.

For Cirillo, contemporaneous church music failed to move the hearts of the listeners to a deeper love for God, and this mirrored the failures of a part of the Church as such to inspire a more profound devotion. He was not pessimistic, however, and he hoped for an interior reformation: both the Church and her music had to recover the wisdom of the ages, and thus hopefully reach new heights in their respective arts of beauty and holiness.

From awareness of this need for a reform of the Church and of her music sprouted all the Reformations – both Catholic and Protestant – of the sixteenth century: in the following articles, we will discover the shapes they took and how they expressed themselves in music.

Dr Chiara Bertoglio is a musician, a musicologist and a theologian writing from Italy. She is particularly interested in the relationships between music and the Christian faith, and has written several books on this subject. Her new book, Reforming Music: Music and the Religious Reformations of the Sixteenth Century, is due to be published in April by De Gruyter. Visit her website

Earlier articles: (1) Reforming music: harmony and discord in the 16th century (2) Pre-Reformation church music: plainchant, polyphony and popular songs

Profile image is Ferdinand van Kessel's "Cats Concert" (cropped) via Wkigallery.org. Not for commercial use.

March 24, 2017

Do people still have car stickers? I had a “Nuclear free New Zealand” sticker on the rear window of my first car for a while, but resisted efforts to have me advertise other causes after that. Flaunting a slogan to people you will never meet may annoy them rather than convince them that there are some good arguments for it. It’s more likely to communicate that you have a fixed, ideological position on an issue and that nothing will change your stance. I was going to say, “change your mind,” but that suggests it was thought-out in the first place, which is precisely what’s lacking in ideology.

This is the issue that Randall Smith addresses today in our Public Discourse essay. At a time when the air is thick with slogans, he helpfully distinguishes the characteristic marks of an “ideology” versus a “principled position.” Here’s a taste:

One way of always being right is to stop up your ears and scream. The other way is by doing what Socrates did: spend a lot of time patiently talking to others, testing your own ideas and listening to the best evidence from others to see whether your thoughts and words correspond to reality in all its fullness and complexity.

Amen to that.

Which reminds me: some, perhaps many of us will be attending a church service over the weekend. And a Sunday service means music – singing, choir, instruments – which may bring joy, or, in some cases, a certain amount of pain. Apparently, it was ever thus. In her third article on music in the Reformation era, Chiara Bertoglio gives a sample of the often hilarious critiques of church choirs in the Renaissance period – complaints that, for me at least, strike a chord.

I do recommend Chiara's articles, which are based on a book she has written for this Reformation anniversary year and is due out next month.

I do recommend Chiara's articles, which are based on a book she has written for this Reformation anniversary year and is due out next month.

Carolyn Moynihan

Deputy Editor,

MERCATORNET

| How to spot an ideologue By Randall Smith Ideology and the corruption of language. Read the full article |  |

| How the Virgin Mary brings together different faiths in Pakistan and India By Donna Fernandes A famous Indian shrine is at the epicentre of devotion. Read the full article |  |

| Polyphony? Or cacophany? Prelude to a reformation in church music By Chiara Bertoglio ‘Bleating’, ‘howling’ and ‘whinnying’: Renaissance critics on church choirs. Read the full article |  |

| French fertility declining, but still highest in the EU By Marcus Roberts France's population could outstrip Germany's in time. Read the full article |  |

| The politics of grievance is a dead end By Ronnie Smith Scotland, clinging to the EU, currently illustrates the point. Read the full article |  |

| What’s the secret of the world’s happiest countries? By Carolyn Moynihan Judging by a new study it might be as prosaic as popping a pill. Read the full article |  |

| Parental leave for grandparents By Shannon Roberts Cuba is desperate for babies. Read the full article | .jpg) |

| Africa is topping the right lists By Mathew Otieno The continent ranks ahead of the world in some good things too. Read the full article |  |

| Addiction or compulsion: our love/hate relationship with technology By Heather Zeiger Is existential angst driving us to connect? Read the full article |  |

| Sticky competition spoils maple syrup harvest By Jennifer Minicus A new Pumpkin Falls mystery Read the full article |  |

MERCATORNET | New Media Foundation

Suite 12A, Level 2, 5 George Street, North Strathfied NSW 2137, Australia

Designed by elleston

New Media Foundation | Suite 12A, Level 2, 5 George St | North Strathfield NSW 2137 | AUSTRALIA | +61 2 8005 8605

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario