Star-studded CVs and moral numbness

The prevailing wisdom is that well-trained professionals will contribute towards social welfare and environmental sustainability. That's not the way it works.

If one does a simple web search for corporate fraud, financial scandals, aggressive marketing of toxic products or other forms of corporate malfeasance, we get a list of some of the biggest names in the industry. Be it oil companies, financial institutes, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, auditing firms, consulting giants, or fast food companies, hardly any big name seems to be giving this party a miss.

We are as concerned with the scale of these malpractices as we are with the real-life impact of these activities on society. For the impact of fraud and wilful disasters of the oil companies, we find permanent ecological damage, destruction of biodiversity, loss of habitat and poorer health quality of all human and other life. Fatal addictions, commerciogenic malnutrition and over-medication from the pharma and fast food industries. The loss of health and healthcare, loss of employment or inhumane working conditions for others. The ravages of natural resource and human exploitation, war and violent conflict are known to be intricately linked with profiteering armaments’ manufacturers and global finance. Connecting the dots is not that difficult. What amazes us is that these are the very industries and big-name companies that hire the best talent usually from the country’s most elite institutions.

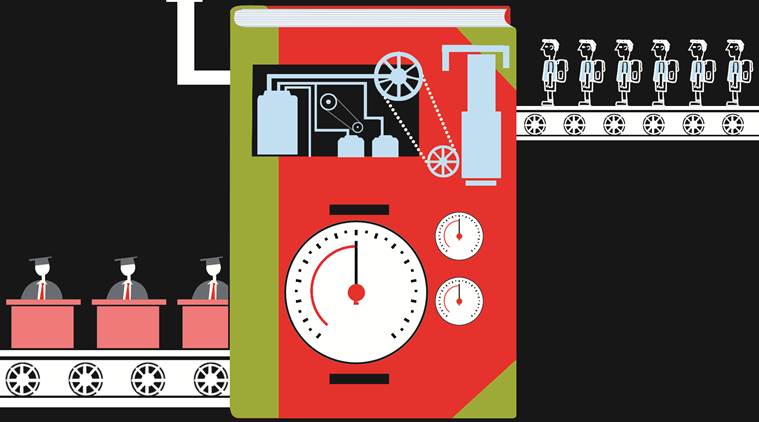

Paradoxically, the common perception in such institutions is rather different. Here, the prevailing wisdom is that well-trained professionals will contribute towards social welfare and environmental sustainability. This seems so remarkably at odds with the situation we have spelt out above. However, if we see such elite training grounds a little differently, we feel that such a paradox will no longer remain a mystery.

The answer, we feel, lies in the social norms and cultures of disciplining towards which educational spaces are geared today. It is in these spaces that potentially smart individuals are transformed into compliant “professionals”, who focus merely on executing instructions in the most efficient manner. The incentive structure (status, prestige and pay packages associated with the firms who value these individuals as potential employees) is designed in such a way that the individuals lose interest in questioning the status quo, in seeking explanations, or in doing things differently — they look for standardisation, seek comfort in given structures, and limit themselves to task-orientation. The pedagogy in these “schools” is designed in such a way that the students learn to follow a solution-first approach — they are trained to solve the given problems in an instantaneous manner. In a quest to be the first one, they hardly question what they’re being asked to do, but quickly rush into “solving” problems, irrespective of the larger implications of their actions. A classroom exercise in one of our courses can illustrate this clearly

In this activity, the students were asked to form a group of two or three members to discuss the following: “Identify a product or service that you would ‘sell’ with all your energy, talent, and creative resources (with an intent to expose, attract, have people try, consume and ultimately seek their addiction), but would use that same level of energy in order to insulate and protect your family members, and ensure that they don’t consume the product or service in question.”

After some discussion, the groups identified certain products that were either proven to be harmful or were perceived to be potentially harmful — dating apps for married people, violent and sexualised video games, pornography, euthanasia, prostitution, junk food, soft drinks, energy drinks, muscle building supplements, alcohol, cigarettes, and many more.

From the perspective of a participating student, one of us noted: “As soon as the question was presented to the class, my group members and I started thinking of products that were harmful, addictive or illegal. We felt that it had to be a ‘bad’ product because we were asked to keep our families away from it. We started thinking of cigarettes, marijuana, and dating apps for married people. There was a lot of enthusiasm and we started discussing how we would position the product in the market in order to achieve maximum sales, but at the same time, we were sure that we would shield our family members from the product. Till this point, there was absolutely no feeling of immorality or wrongdoing. We felt we were only trying to solve a problem. After much discussion, one of the class members mentioned that such a product should not exist — if all of us start marketing aggressively, then eventually our families would also be exposed to the harmful products. At this point, the entire course of the discussion changed from marketing strategies to business ethics. I felt uneasy and disturbed as I realised that I was so sincere and diligent about solving the given problem that I had completely lost out on my ethical lens. I felt guilty and embarrassed — that it took a great deal of facilitation to make me and other class members realise that we were actively pushing for something that we ourselves considered harmful or immoral. I was also a little bewildered as I am not someone who would place business gains or my loyalty towards my employer above my conscience or morality. However, that’s exactly what I did, albeit, subconsciously.”

It should have been obvious that the exercise presented an ethical dilemma, and could not be tackled like a calculus problem. But as it actually transpired, the students believed that there was nothing right or wrong in the solutions proposed by them — it was not about a moral choice, and it was purely a business strategy. More so, the students displayed an abstract, but remarkably strong, sense of employer attachment. They felt that their foremost identity as an employee should be to take care of their employer’s interest. They spoke of this loyalty in a sacred manner — as if it was preordained, and should not be subject to any sort of interrogation. Another serious rationalisation was the belief that nothing was actually going to change, by any intervention or questioning from their side.

We wonder if there is a way to “un-school” well-intentioned individuals, to enable them to discern the real-world implications of their powerpoints and excels — to nurture individuals to think critically, to raise questions, and to seek explanations, as opposed to the current culture of training individuals into diligent and obedient employees. However, this begs an important question. Would instilling moral criticality through pedagogical interventions (such as the classroom activity) be in line with creating “employable” resources, or would that be in contradiction to the interests of corporations that recruit well-witted disciplined individuals who strive endlessly to “strategically” maximise their employers’ profits? We’re not sure where we can get the answer from, but the bigger worry is that not many seem to be asking this question.

Dhamija was an MBA student, batch of 2016, at IIM-Ahmedabad and is an entrepreneur. Mathur is faculty member, public systems group, IIM-A

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario