The dancer and the dance

Caste and gender hold the key to understand the politics that unites parties in opposing dance bars in Mumbai.

The Supreme Court has yet again ruled against the Maharashtra government’s ban on dance bars in Mumbai. It has said that the government cannot impose its morality on an unwilling society. Time and again, the courts have addressed the legal and political dilemmas around this ban. For example, in October 2015, the Supreme Court stayed the Maharashtra government’s 2014 legislation pertaining to dance bars. It stated that the new legislation was not very different from the 2005 version held unconstitutional by the apex court in July 2013. There is apprehension that the government may yet again try to not lift the ban. What explains the agreement among all political parties that dance bars must not allowed to open?

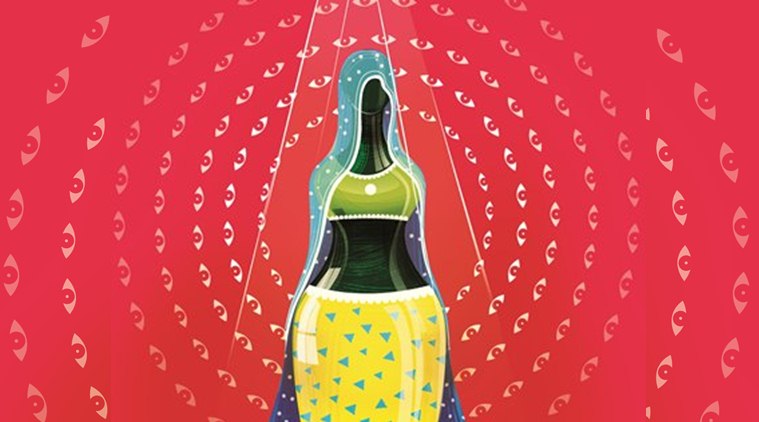

The demand for the ban came disguised as discourses of gender rooted in nationalism, culture and the dignity of women. The state was called upon to protect the family and the good wives, the helpless youth and the Maharashtrian/Indian culture from the dangerous lure of bargirls. In the Maharashtra legislature, the need for a new law was justified as a need to discourage men from going to the bars and throwing money at ‘bad women’. In this scheme, the upper caste/class men seemed to need the protection of the state from the lower caste/class women. The bargirls became the ‘bad women’ who danced before men and seduced them with obscene attire and gestures. They were accused of avoiding honest labour and earning ‘easy money’, unlike the toiling, good poor women.

Caste and gender hold the key to understand the politics that unites parties on the dance bars issue. The emergence as well as the ban of dance bars in Mumbai can be seen as symptoms of globalisation in India. Dance bars emerged as a site of opportunity for customers to flaunt the wealth they had accumulated through their association with a globalised India. For the bar dancers, a majority of who came from the traditional dancing communities of North India, it offered a new employment opportunity. The demand and supply sides of dance bars comprised two distinct classes, which fit uncomfortably into the narrative on globalisation in India. The first class is the vernacular “new rich”, linked to the black economy, government contracts, political connections and religious consumerism. This class constitutes the bulk of customers of the dance bars. The second class comprises the lowly-paid irregular workers; a class of people who are not just poor but are surviving with limited means. Bargirls hail from this class. Since the 1980s, these two classes have come together to create the dance bar market, which has upset and irritated both the ruling ideology as well as the popular script of globalisation.

The dance bar market offered its customers song, dance, Bollywood imagery and a pretence of royal mannerisms in the tawaif culture. It enabled customers to escape reality, feel like royalty, and fulfil the need for affirmation of their new status that the seemingly charmless capitalist economy — while providing unprecedented cash — fails to provide.

The dance bars used the power of musical performance in arousing feelings and deployed the established idiom of the Hindi film songs to attract customers to the bar and the bargirls. For customers, the dance bars offered a sense of fantasy, drama, adventure, addiction and competition. Though the dance bars were lucrative, they had remained almost hidden from the mainstream public for nearly two decades.

The bar dancers from traditional dancing communities can be seen as “performing their castes”: They were redeploying their caste capital — skills of dancing, entertainment, care, hospitality and the use of sexuality — to occupy the new space created by the globalising dance bar market. However, as their traditional skills gained unprecedented demand and monetary value in the globalising market, the bargirls seemed to occupy a space of high economic gain and challenge the gender, caste, class borders by performing their caste occupation in the global market.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario