Online platforms could lose India’s youth if they continue self-censorship

It couldn’t be made clearer that the Indian audience provides immense market opportunities for platforms which can grant them the “neem ke patte” that have traditionally been censored from Indian films and TV shows.

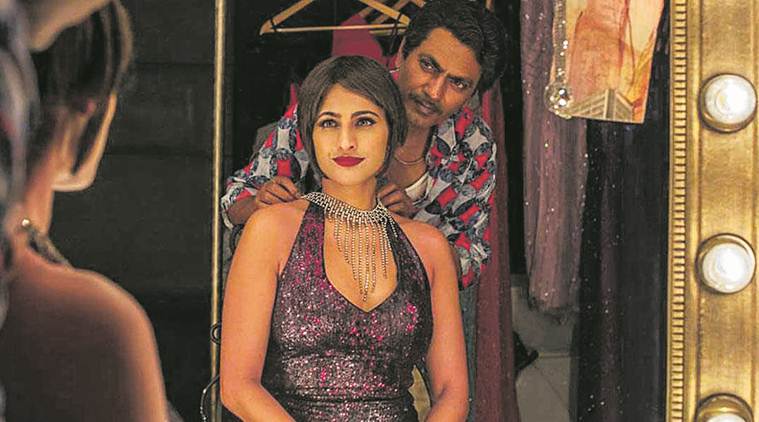

“Neem ke patte karwe sahi, kamsekam khoon to saaf karte hain (Neem leaves might be bitter, but at least they purify blood),” says Nawazuddin Siddiqui as Manto, the eponymous protagonist of a biopic on the writer Saadat Hasan Manto released last year. The film, written and directed by Nandita Das, addresses the theme of freedom of speech and expression. Manto, now a celebrated author, was then criticised and prosecuted for the allegedly “immoral’ and “provocative” nature of his stories. It is this allegedly profane content that he refers to as “neem ke patte”. In the film, Manto defends his work, stating that what he writes is only a reflection of what he sees around him and that denying this reality does not make us any more humane as a society.

We don’t seem to have made a lot of progress since the post-Partition era. Recent reports indicate that popular over the top (OTT) platforms such as Amazon Prime, Netflix and Hotstar have begun self-censoring their content.

When Sacred Games, the first Indian series produced by Netflix came out, it was met with critical acclaim — many lauded the show as the Narcos of India. Personally, I would hesitate in placing the show at par with Narcos and do not believe that it was extraordinary in it’s storytelling. However, I believe that the show’s significance lies in the content that it doles out to its viewers. I was grateful for, and pleasantly surprised by, the limits to which the show pushed the envelope with regards to what a conventional Indian show could contain. With its brazen and uncensored content, replete not only with abusive language, violence and nudity — an exciting currency for India’s maturing young viewership — but also stark political upfrontery, the show marked the advent of a new horizon in Indian television. Soon, Netflix’s Lust Stories and Amazon Prime’s Mirzapur followed suit.

This new viewership has since become attuned to content unfettered by the morality imposed by traditional censorship bodies. We, as viewers, now welcome platforms that — by providing myriad choices in consumption — refuse to infantilise us and offer us an alternative to mainstream cinema. The Indian film industry is still limited by the prudish sensibility of the Central Board of Film Certification. Further, OTT platforms have changed the ways in which we consume films. The shift from big screens to smaller digital screens has led to the private consumption of material, allowing individuals to watch what they want without supervision and the accompanying fear of retribution.

Therefore, these platforms’ decision to pre-emptively censor themselves is extremely disheartening, especially given that there exists no comprehensive policy regarding the censorship of online content in India, nor has the government announced any concrete plans to set up a regulatory body for cyber content in the near future. Amazon Prime, it has been reported, has been self-censoring Indian films that contain mature content. Not only are certain dialogues muted in films such as The Dirty Picture and Hunterrr, the duration of the films is much shorter than the version of the films available on rival OTT platform Netflix, making it evident that many scenes deemed inappropriate have been cut out from the films.

It is speculated that this pre-emptive censorship comes as a response to a flurry of recently filed petitions by individuals and NGO’s demanding censorship of “profane” online content. In keeping with this, in October of last year, the Nagpur Bench of the Bombay High Court urged the Centre to respond to a similar plea for censorship.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario