The techno dystopia

Controversy over EVMs shows that regulatory structures are needed to ensure the algorithmic world doesn’t trample on democratic rights.

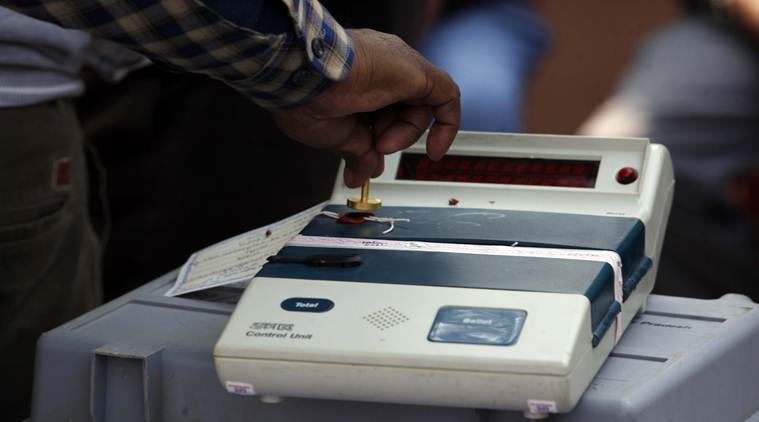

Two former chief election commissioners (CECs) and the current CEC have verbally, and in writing, rebutted the suggestion that the electronic voting machine (EVM) is hackable and that the Commission should safeguard public franchise by reverting to a form of paper balloting. This controversy is about the electoral process in India. It bears, however, upon a deeper issue. The tension between technocracy and democracy.

The disclosure that Facebook had allowed the consultant firm Cambridge Analytica to access the private data of its users which was then passed onto the Donald Trump election campaign raised concerns about data privacy and, more fundamentally, the power of the owners of data to abridge democratic rights. The most eloquent votary of this concern has been the historian, Yuval Noah Harari. In a talk at Davos in 2018 followed by other lectures and his latest book, 21 lessons for the 21st century, Harari has spelt out the potential consequences of an algorithmic world. He acknowledged the huge benefits of the digital age but forewarned of a scenario in which human beings acquire the potential to “hack into the bodies, minds and brains of other human beings” and where algorithms “know individuals better than the individual knows himself”. This scenario is imaginable because of the advancement in computing power (info tech) and the agglomeration of biometric and biological data (biotech). When the two “tech” revolutions merge, the handful of companies that own data will fashion the greatest revolution ever overturning the laws of Darwinian selection with the “laws of intelligent design”. Democracy could be replaced by “digital dictatorship” .

Fascinating, science fiction, alarmist — one may use any one or a combination of these words to describe Harari’s prognostications. But there is no ignoring the many questions that his description of an alternative future has raised. Practical questions: What regulatory checks and balances should be imposed on the companies that monopolise data — Amazon, Google, Tencent, Alibaba, Facebook? Should these companies be broken up? If so, who should be given the authority to keep data and to decide how and in what manner this asset should be given away? Surely not the politicians.

Philosophical questions: How does one control phenomena (technology and data) that is “everywhere but nowhere,” that recognises no physical or political barriers and is universal in scope and impact? Can an algorithmic world be managed through institutional structures of governance built on the bedrock of Westphalian principles? (The treaties of Westphalia, between 1644 and 1648, brought to an end the religious wars in Europe. They established three principles that still define the nature of international affairs today — the principle of state sovereignty, non interference in the affairs of other states, and the principle of the legal equality of states)

Harari admits he does not have the answers to these questions. He believes that a collective of poets, philosophers and statesmen should be tasked to develop the answers. Whether that should be the way forward or not can be debated. But what is becoming clear is that questions like those posed above cannot be answered by drawing on the past or projecting from the present. An “out of the box”, approach is required that recognises that technology and innovation have not been an unmixed blessing and that the current rules, institutions and structures of governance will need to be refashioned.

The Industrial Revolution laid the foundation for decades of sustained development and economic prosperity. But it also led to the crisis of global warming. Nuclear scientists generated the prospects of clean, affordable and abundant energy but they also raised the spectre of a thermonuclear holocaust. The digital revolution opened up phenomenal vistas of knowledge and information but, as suggested by Harari, created the potential of digital dictatorship. The issue is that whilst humanity has harnessed the benefits of technology and innovation, it has not yet created the institutions for managing its consequences.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario