Written by Shaji Vikraman |Chennai |Updated: February 19, 2019 8:10:49 am

Simply put: Should we worry of recession?

Economics Nobel winner Paul Krugman warns that the US could possibly be heading for a recession. Amid slowdown in Europe, how strong are the grounds for such fears in the US, and what can it mean for India?

In August-September last year, much of the commentary about a decade of the global financial crisis of 2008 featured the global recovery and the rebound in the United States economy. The bounce-back was strong enough for the US Federal Reserve to signal two rate cuts in 2019 and for global central banks to give notice that a prolonged phase of easy money was coming to an end. Did all of them speak a little too soon? A few days ago, Nobel laureate Paul Krugman sounded a warning in Dubai when he told Bloomberg that the world’s biggest economy, the US, could be heading for a recession late in 2019 or in 2020. “I couldn’t be definitive, but it seems pretty likely,” he said.

What is the ground for such fears?

According to Krugman, the US is in worse shape than it was in 2008. What the economist was apparently referring to is the country’s huge public debt which, at a little over $22 trillion, has been growing over the last few years, and debt-to-GDP ratio — a measure of the ability of a country to repay debt — rising to 104% now. He is looking at a recession also because of the slowdown in Europe, where economic powerhouse Germany has been hit because of tariff wars involving the US and China, a recession in Italy, and slowing growth in France.

“Europe is clearly experiencing a slowdown to recessionary levels already and has no recourse. Draghi (chief of the European central bank ECB) can’t cut rates because they are negative already. So I think Europe is in a danger spot, potentially as big as China,” Krugman told Bloomberg. The worry regarding China is the trade war with the US which, if not settled, could dampen growth or stoke a recession, according to some. The other reason for Krugman to be downbeat is the current US leadership including the US Treasury Secretary — whom he contrasts with the “remarkable” leadership during the 2008 global financial crisis.

The pessimism also stems from Krugman’s reading as well as that of another doomsday predictor, economist Nouriel Roubini (who wrote in September 2018 in Project Syndicate that in 2020, conditions would be ripe for a financial crisis followed by a global recession). Like Krugman, Roubini also believes that trade disputes, an unsustainable stimulus and a massive public debt will leave little room for a stimulus the next time around. That is because the top central banks of the world may not have the firepower to cushion the impact of a recession, having bought massively into bonds and other assets during the global financial crisis to combat that and to ensure easy money. In short, what the doomsday predictions point to is that the top global central banks may not have the policy tools to provide easy liquidity given the liabilities on their balance sheets.

Are the fears overblown?

US President Donald Trump may still be euphoric about the world’s biggest economy (at a growth of 4%) but it is interesting to weigh what Jerome Powell, the chairman of the US Federal Reserve, the world’s most powerful central bank, had to say in January, at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association, where he was flanked by two of his predecessors, Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke.

The US economy is in strong shape but the market was pricing in downside risks that weren’t visible yet, according to Powell. Inflation is still muted and the jobs or labour market is still strong, with high-frequency data yet to mirror some of these worries and with asset prices picking up. The monetary policy of the European Central Bank, or the Bank of England, too is accommodative at this point — a far cry from the time last year when most bets were on them moving towards raising interest rates. The normalisation of policy or a return to the policy before the era of cheap money dating to 2008 appears to be a couple of quarters away.

Krugman and Roubini may not be convinced but Powell said last month that the US Federal Reserve will be prepared to adjust policy quickly and flexibly, and to use all its policy tools to support the economy, should that be appropriate, to keep expansion on track, the labour market strong and inflation close to 2%. What he has indicated is that the central bank will be on course to change tack as it did in 2016 when, after signalling the possibility of multiple rate increases, it settled for just one because of the underlying economic conditions.

Could the predictions be wrong?

Roubini, who earned the name “Dr Doom” after famously calling the 2008 housing bubble in the US, is seen as being cynical. For those worried about the forecasts of a “perfect storm” in 2020, there may be some comfort. Krugman himself admits that he has been wrong in the past. “My track record is bad,” CNBC has quoted him as saying.

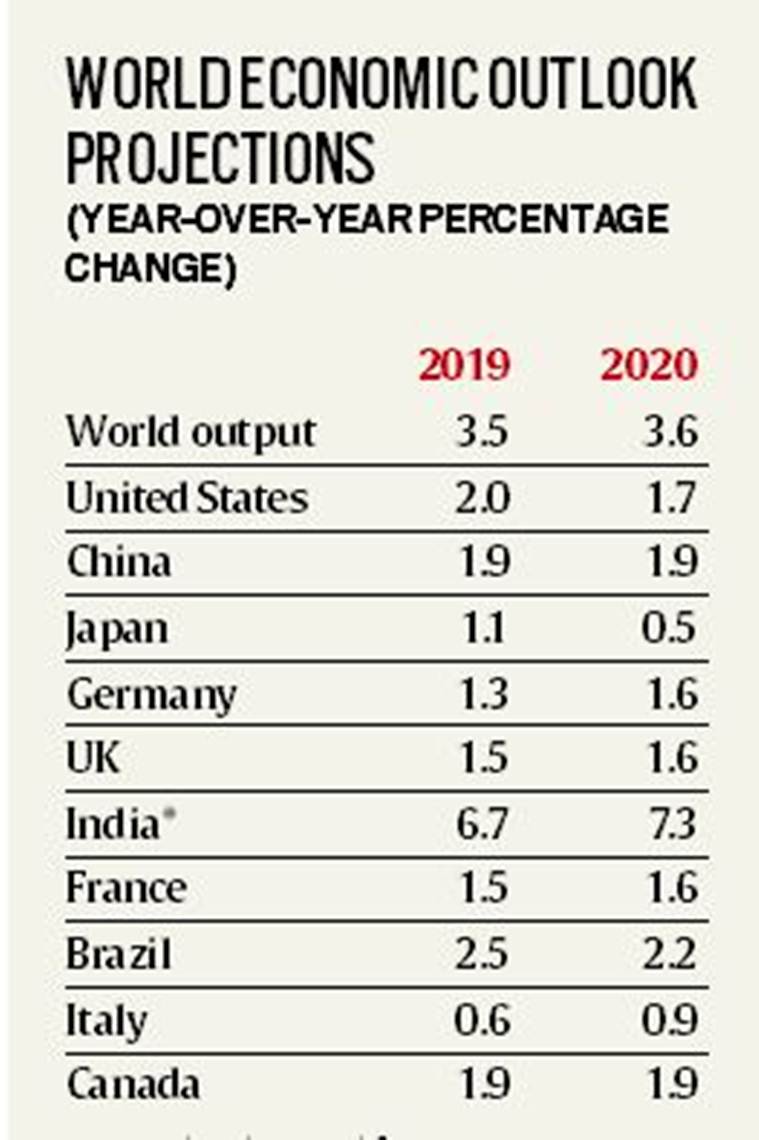

(For India, data and forecasts are presented on a fiscal year basis and GDP from 2011 onward is based on GDP at market prices with FY2011/12 as a base year. Source: IMF)

Where does all that leave India?

An upside of the current scenario, marked by low interest rates and an accommodative policy of central banks and low inflation, will be that the RBI could have more room for cutting interest rates further. Oil prices, a major threat to macroeconomic stability, have been relatively low. Foreign flows have ebbed for quite a while with domestic investors putting money into stocks and mutual funds. That has also seen a slide, but once the political uncertainty is over after the Lok Sabha polls and there is clarity on policies and the direction of reforms and measures to address agrarian distress, the tide could change. That would also be contingent on getting the fisc back in shape, and any near-term impact in the wake of the terrorist attack in Kashmir.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario