History headline: India’s story, through its Budgets

All these pronouncements by successive finance ministers in their Budget speeches will be put to test in the years to come.

IN the opening note of his book A View From the Outside: Why Good Economics Works For Everyone (2007), a collection of columns he wrote for The Indian Express between August 2002 and March 2004, former finance minister P Chidambaram noted that Budgets, which once had inviolable sanctity, had over time become a bag of tricks for governments, and the figures they contained had lost much of their meaning. And interim budgets now go beyond just spending allocations for the first four months of the new fiscal before a new government takes over.

Over the seven decades of the Republic, the presentation of the Budget has remained one of the most important events in the country’s economic calendar. Unlike in Western countries that have shrunk the Budget to just a statement of annual revenues and expenditure, India, with its federal structure and wide disparities, has abided with a lengthy and complex procedure that offers a broad indication of the policy direction of the government.

Besides the expenditure and revenue budget — which is among the earliest to be printed in the captive press in the basement of North Block that houses the Finance Ministry — there is the speech of the Finance Minister, a receipts budget, and a medium-term fiscal policy statement.

Because much is at stake in the Budget, both politically and in terms of the economy, finance ministers have a series of meetings with the Prime Minister to first get a broad direction and to then discuss the major proposals, especially the ones that can be politically sensitive.

The breadth and depth of intervention differs from PM to PM. Ahead of the so-called ‘Dream Budget’ of February 1997, when finance minister Chidambaram went to the United Front prime minister H D Deve Gowda with his radical proposal for three tax rates — 10 per cent, 20 per cent and 30 per cent — Gowda just said, “Let’s do it. Don’t (be) afraid!” As Chidambaram put it later, it was a policy equivalent of slog overs in cricket — going for broke.

The breadth and depth of intervention differs from PM to PM. Ahead of the so-called ‘Dream Budget’ of February 1997, when finance minister Chidambaram went to the United Front prime minister H D Deve Gowda with his radical proposal for three tax rates — 10 per cent, 20 per cent and 30 per cent — Gowda just said, “Let’s do it. Don’t (be) afraid!” As Chidambaram put it later, it was a policy equivalent of slog overs in cricket — going for broke.

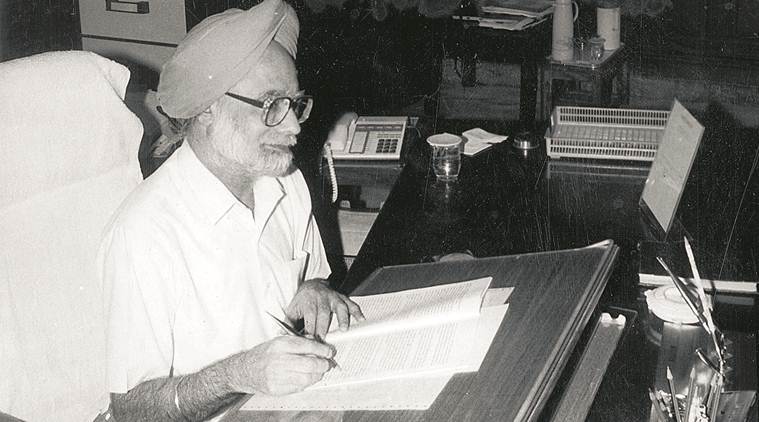

With the country teetering on the brink of an economic precipice, prime minister P V Narasimha Rao threw his political backing behind his finance minister’s historic July 24, 1991, Budget. Manmohan Singh famously invoked Victor Hugo — “No power on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come… Let the whole world hear it loud and clear. India is now wide awake” — and announced proposals that began the unshackling of the Indian economy.

As the Budget proposals for 1999-2000 were being finalised, prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee underlined to finance minister Yashwant Sinha the importance of following the principles of a rule-based, non-discretionary tax system — “siddhant se kariye”.

A year earlier, he had advised Sinha to give priority to the rural sector and farmers, and to ensure that the Budget proposals were non-inflationary.

A year earlier, he had advised Sinha to give priority to the rural sector and farmers, and to ensure that the Budget proposals were non-inflationary.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario