View from city’s margins

Among urban poor, demonetisation has taken an untold toll. Government schemes are a mixed blessing

Thus far, this column has analysed politics and the political economy. When it has departed from that self-imposed norm, it has experimented with two alternative formats: Conversations with leading specialists, who know more than I on a given topic; and travel reportage.

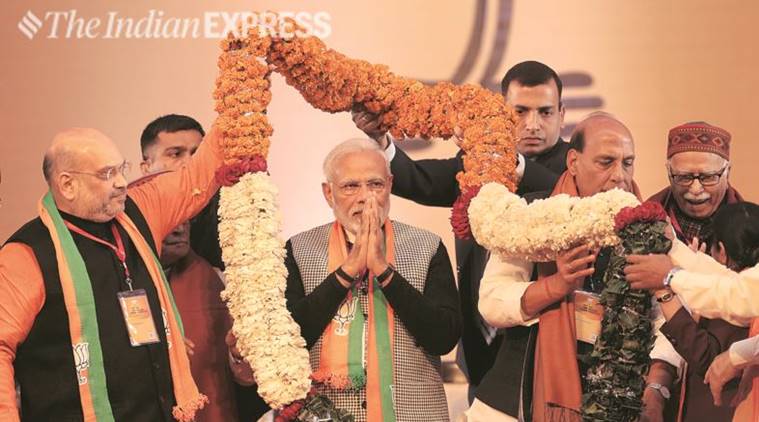

My travel reports have thus far been from China. This column debuts reportage on my India travels. There will be more in the upcoming election cycle, when I follow Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s campaign, especially in Uttar Pradesh, a state I grew up in — in towns like Shahjahanpur, Faizabad, Rae Bareli, Hamirpur, Agra, Aligarh, Allahabad. These were my habitats before I moved to Delhi and later to the US, from where I have routinely come to India for three months a year.

Over the last 12 months, my research project on urban governance — on determinants of urban public services (water, sanitation, electricity, roads, education, health, policing) — has taken me to Chennai, Kochi, Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Bhavnagar, Mumbai and Hyderabad. Next year the project will move to the north and east. Before we commission large quantitative surveys on urban governance, we do qualitative work for a few days in each city. We talk to the elite (politicians, bureaucrats, police officers, NGOs) and the masses (primarily slum dwellers). We have now covered 21 slums in southern and western cities.

While statistical results based on representative samples will be analysed later, observations on some of the key programmes of the Modi government are worth registering. Election specialists believe that Modi was extremely popular among the urban poor in 2014. While that claim cannot be extended to Chennai and Kochi, where the BJP was a minor player, it applied to western and northern cities and even southern cities like Hyderabad and Bangalore. That is not true anymore. Modi critics far outmatch Modi supporters. I am not simply talking of Muslims living in slums, but also Dalits and OBCs. Scepticism and disappointment are widespread.

Why is that so?

First and foremost, demonetisation was extremely painful. Poor households ran out of money, the lines were too long, and at the end of the wait, banks would not have enough legal currency for exchange. Children went without enough food, and the older folk often did not have adequate medication. It remains an enduring mystery how the BJP won UP so decisively soon after demonetisation. But one must also quickly recall how close the Gujarat results were in December 2017 and how the BJP was defeated in its strongholds of Rajasthan, MP and Chhattisgarh in December 2018. In the last three, the data show that the BJP’s urban vote declined, not simply its rural vote. Urban middle classes might still want Modi, but the urban poor have almost certainly played a big role in Modi’s declining performance. Demonetisation inflicted untold misery and suffering.

The Swachh Bharat (Clean India) campaign also does not come out looking good in the slums we covered. It might have done well in rural India, as the available independent analyses clearly suggest. But in urban India, the results appear to be highly mixed. Whatever Swachh Bharat has done for garbage removal, its toilet scheme can’t easily work in the slums of large cities like Mumbai and Hyderabad. If you live in a one-room dwelling, a family toilet simply cannot be built. Community toilets, not family toilets, are your only recourse, and as far as we could tell, Swachh

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario