The Flesh Made Word

The autobiography tries to understand the life of the mind in relation to the body

You are probably familiar with the classic expressions of mind-body dualism, where the mind merits all meaning and value, and the body finds itself reduced to no more than meat. It’s a central claim, for example, of French philosopher Rene Descartes: “I conclude that my essence consists solely in that I am a thinking thing, or a substance the nature of which is nothing but thinking. And though I have a body with which I am very tightly conjoint, nevertheless it is certain that I am truly distinct from my body, and could even exist without it”.

The claim is often belied by our ordinary experiences. Try to pick your thinking self up from a chair after age 45 and see how “truly distinct” you are from your body. There is also the testimony of others, found most profoundly in autobiographies.

The claim is often belied by our ordinary experiences. Try to pick your thinking self up from a chair after age 45 and see how “truly distinct” you are from your body. There is also the testimony of others, found most profoundly in autobiographies.

Autobiographies tend to reveal the physical, the material conditions that gave birth to the spirit of their authors. Generally, we know these authors on account of the lofty representations of their mind and spirit from media reports, literary criticism, history books, and so on. But autobiographies reveal first-person lived experiences. They render all the high ideas that we readers have about their authors concrete. They suture together spirit with its underlying flesh.

Yet there is a grave difficulty lying hidden here. The unity that is sought presumes the that age-old duality of flesh and spirit, body and mind. It is precisely this problem that philosophers of the self are attempting to tackle. For them, predominantly materialists, persons may be substantive selves, minimal selves, narrative selves, interpersonal selves, and so on. But the term “flesh”, indeed, even the word “body”, is always used with great reluctance. Whatever body is for philosophers of the self, it functions as scarcely more than an informant — neural connections are what really matter. So what happened to the flesh of the autobiographical self? Why are philosophers of the self as reluctant as cognitive scientists to linger over it?

Perhaps this is because of the long run that Catholic theologians enjoyed with it. First, they took charge of the body, filling it with nothing less than the symbolics of Christ (“And the Word became Flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14)). Then they took over autobiography as the definitive confession. So how ought we — at least, those of us who are not Cartesians or who do not subscribe to the Catholic faith — to understand the life of the mind with relation to the body, or vice versa? Does the philosophy of the self have the answers?

It certainly has many. However, I believe that without turning to autobiographies we will never be granted the complete kind of access that we need in order to think trenchantly and comprehensively about this kind of a question. It may only be in the narratives of real, lived experiences where genuine insights begin to more fully emerge.

It certainly has many. However, I believe that without turning to autobiographies we will never be granted the complete kind of access that we need in order to think trenchantly and comprehensively about this kind of a question. It may only be in the narratives of real, lived experiences where genuine insights begin to more fully emerge.

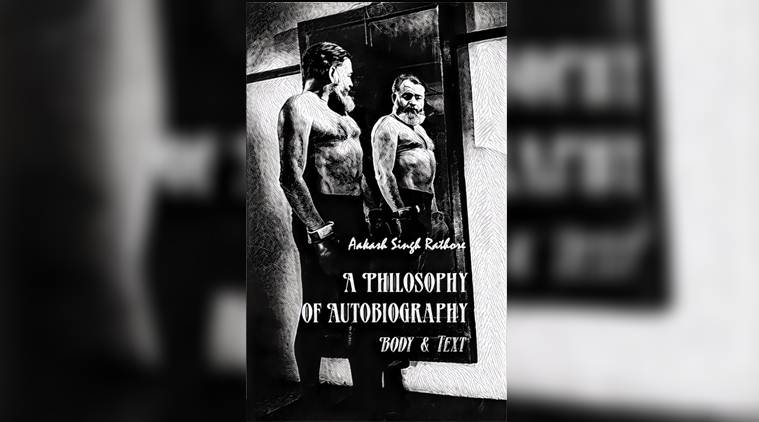

In my new book, A Philosophy of Autobiography: Body & Text, I look at the autobiographies of iconic men and women (Nietzsche, Gandhi, Ambedkar, Maya Angelou, Ernest Hemingway, Elie Wiesel, Daya Pawar, Kamala Das, Yukio Mishima, Andy Warhol, and others). They depict the relationship between flesh and spirit in their experience and understanding.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario