Not the EVM again

The accusers swap places with accused, and a contrived controversy goes on

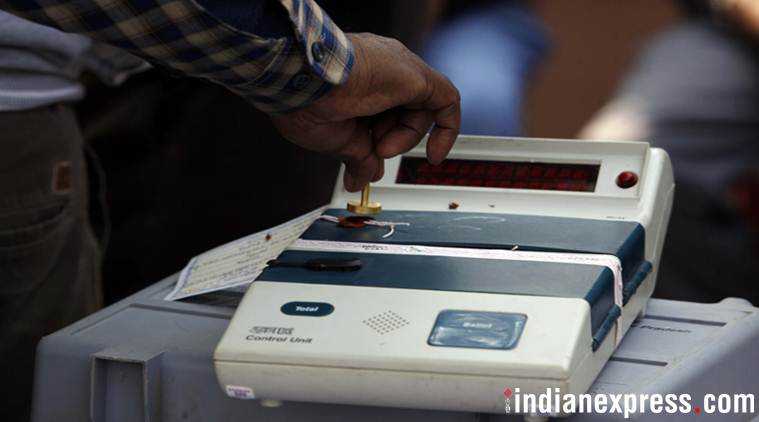

The EVM debate is back — yet again! This is one controversy that refuses to die down, raising its head every few months. This time around, its epicentre was London. What was promised as a sensational demonstration of hacking by “cyber experts” from the US that would cause an earthquake ended as poor melodrama with an anti-climax.

The “cyber expert” was one Syed Shuja, who claimed that he had taken asylum in US after he and his colleagues were fatally attacked since they knew too much about the “hacking” of the 2014 General Election and were countering it. Several persons, including his teammates, were murdered, he alleged, for the same reason. The “facts” mentioned by Shuja can be independently corroborated and I am sure concerned agencies would be doing their homework, as they must. I will stay with the debate about the hackability of EVMs.

There is a well documented history of such claims. Besides individuals, every political party has raised doubts about these machines at some time or the other and demanded a return to the ballot paper. But they have also won elections with the same machines.

Can ballot papers really change the picture? In July 2010, when the Telangana agitation was at its peak and 12 MLAs of the Andhra Pradesh Assembly resigned and recontested the by-elections on the issue, that was the time when the agitation against the EVMs was at its peak, thanks to the BJP’s campaign against EVMs. As the EC had turned down the request of political parties led by the tech-savvy Chandrababu Naidu to revert to ballot papers, the parties resorted to a smart ploy.

Since EVMs are configured to take only 64 candidates, the TRS decided to field more than 64 candidates in each constituency. While Yellareddy in Nizamabad district recorded the maximum of 114 nominations, Sircilla stood second with 107. Even after the large-scale rejection of nominations, the number of candidates left in the fray in six constituencies exceeded 64. This forced the EC to conduct elections in those constituencies by ballot paper, while the remaining six were conducted with EVMs.

As CEC back then, I took it as an opportunity to test and demonstrate the relative strengths of the two systems. While the results from the EVMs came out in four hours, those with ballot papers took 40 hours. On top of that, thousands of invalid votes inevitably happened with ballot papers. In addition, the cost of paper ballots and the prolonged drudgery of the polling staff was an additional burden. What’s more, the results from both systems were exactly the same. So what did they achieve with all the fuss? Zero!

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario