Krishna Sobti: A gateway to Ganga-Jamuni vista

Krishna Sobti’s work exposes the horror of a segregationist regional jingoism.

I was a precocious teenager when I first read Krishna Sobti. My mother gave me her Daar Se Bichhadi (“Separated from the Flock”). Read it and you will see why the Chaudhary family next door looks so sad and lost, she said. The family she referred to was a zamindar family that had been forced to migrate to our little hill town all the way from Deran Gujranwala in Pakistan. Their men had been offered the mosquito-infested Terai lands nearby, which they turned into a lush thriving expanse of farm land. The women though never quite recovered from the trauma. I resented my mother’s interference in my intellectual life. I preferred my own freely chosen books. But when I finally began reading it, the lyrical language laced with Punjabi, the mythic imagery and the love tribulations of women at Partition knocked down my literary defences.

Women, Sobti’s books like Daar Se…, Mitro Marjani, Yaaron ke Yaar and Dil o Danish told me, forget the things melancholic men remember. But they do remember everything they do not want to forget. They then go on to act and do things accordingly. My resistance to dialogue fostered by much of the English fiction I read collapsed before Sobti’s fine ear for colloquial Punjabi or old Delhi’s hybrid speech. Out of the mouths of unlettered women she finds the bliss of wisdom lighly worn and sneeringly dispensed: “Mitro stood watching. Then she clapped her hands and winked at her brother in law, ‘Oh I bow to thee Foolan the queen, I bow to you. Ve Gulzari, your queen has no heart murmurs, nor a belly ache or weakness. This is a deep display of character… This thief Gulzari, is going to rob you of your mind if you remain such a clod!”

“Foolan began to roar like a wounded tigress. Those that find my illness false, may her own life and eyesight go! May her liver burst with pain!”

“Shut the hell up woman, Mitro said to her, cut out the theatrics and try to produce a man child!… Then she began laughing, your mother-in-law is a real cow. Don’t breathe poison before her. I know how you enjoy yourself at night and then create a Mahabharat in daytime!” (Mitro Marjani).

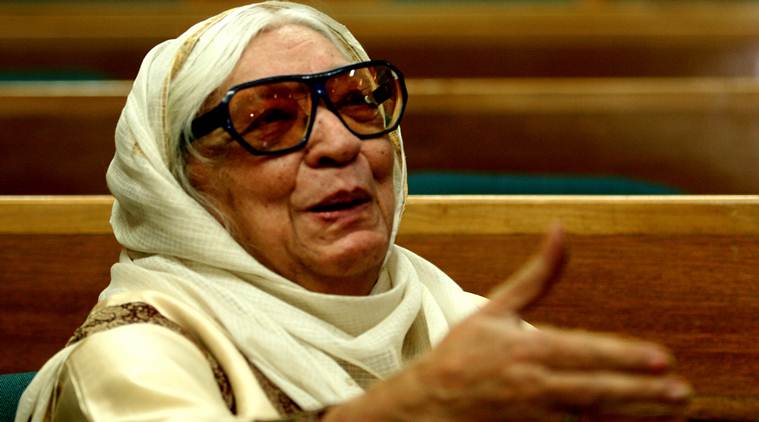

By the time I met her in Delhi, Sobti was already a legend. Short and portly with her signature shades, she dressed in her own kind of sartorial elegance in colourful gharara kurtis and dupattas laced with gold or silver. Her lovely mouth was ever ready to quit its ironic sneer and burst out laughing. She purged the punditry-ridden Hindi literary scene of the 1980s dominated by upper caste men and introduced a wonderful colloquialism that Hindi had been forced to shed post Partition. She brought back to Hindi its regional variations, injecting into it a good dose of robust Punjabiyat, the mellifluous Urdu of Old Delhi and, occasionally, the lilting tones of the East.

Above all, Sobti helped the likes of me to let go of the usual Hindu objections to describing love tribulations of ordinary women. The story of her female protagonists’ progress through several marriages, mistress-ships confronted us with the significant idea that the choices men and women make in choosing partners stretch beyond romance into different values, hopes, argumentative possibilities and sex. The rapture of sex and the excruciating agony of unsatisfied women like Mitro finds unabashed expression in her writing. The good writer, I learnt from her, diagnoses weakness where her protagonists themselves do not feel it, much less describe it clinically. She rejected a neutral universal Hindi and wrote unapologetically in the Punjabi-inflected dialect in which she was raised. Few know today that she was the fountainhead of the Punjabi Hindi Manohar Shyam Joshi’s characters spoke in Buniyad, his fabled serial on Partition.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario