The spy who wasn’t

Nambi Narayanan’s acquittal raises a crucial question: Who is responsible for the evils of the state?

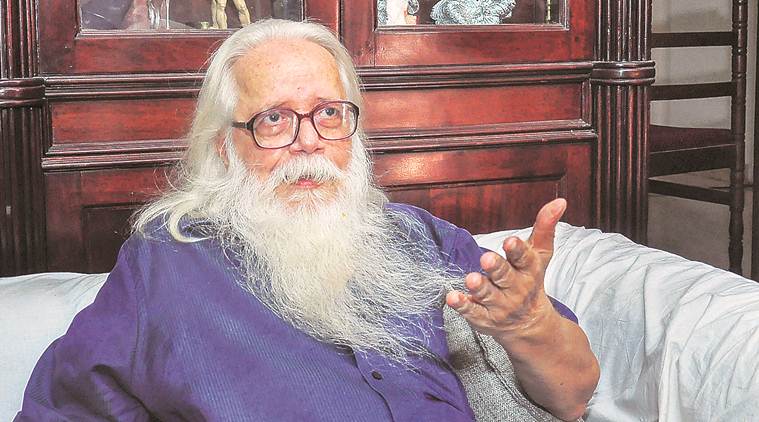

Nambi Narayanan was India’s leading specialist in liquid propulsion engines

Some days ago, the paper carried the news that Nambi Narayanan, the scientist who was accused in the supposed “ISRO spy scandal” and arrested in 1994, has finally been honourably acquitted, and also been awarded Rs 50 lakh as compensation for the damage to his reputation, and his ruined life. The Supreme Court has also ordered an enquiry into the circumstances in which this absurd case was fabricated, and pursued for a quarter century.

However, now that justice is done — or almost — there are a couple of questions that demand address. The first of these relates to the quantum of compensation. What goes into the calculation? Does the distinction of the victim matter — after all, Nambi Narayanan was India’s leading specialist in liquid propulsion engines? But what about the less distinguished others — the nameless, unremembered “undertrials” — who languish in the custody of the state for years, and are then released for want of evidence — without so much as an apology? Perhaps their lives weren’t worth very much before they were picked up by the police? But how much are they worth after they have spent years in custody — not tried, let alone convicted, but merely awaiting the attention of a callous state? There are those who argue that all this merely demonstrates the efficacy of the judicial system — and perhaps it does. But does it not also demonstrate, in case after case, the inefficacy of the police — their unique combination of incompetence, and hyper-efficiency?

Thus, while some people can be picked up in the absence of any evidence whatsoever, certain others can commit crimes in full public view, and even boast about them — except that the police don’t seem to notice?

The other question, even more important, relates to the matter of the financial liability for the “damage” to Nambi Narayanan’s reputation — the five million rupees — and the related question of the sovereign immunity enjoyed by civil servants. To my lay understanding, sovereign immunity can be thought about in two different ways: The first is one wherein the sovereign (state) is immune from the actions of its agents, so that no matter how awful the agents of the state are, and are proved to be, the state itself remains above it all, unbesmirched. The other understanding of sovereign immunity is that wherein the agents of the state, acting as its agents, are immune from legal liability. But if the state transfers its “immunity” to its agents, doesn’t it itself become non-immune, liable, vulnerable to legal interdiction? Or is the state’s “immunity” something like the “love” of the Sufis — the more you give, the more you have?

Because after all, someone has to be liable, to be accountable — or where is the five million coming from? Either the cops and officials who executed this farce pay or the public treasury does. In the latter case, I submit, it is my pocket that is being picked! It is not enough to stand at Jantar Mantar with a placard that says #NotInMyName — because it is precisely in my name that all this is being done. In a democracy, the citizen must be the locus of sovereignty. It is precisely in my name that schoolboys are being blinded with pellet guns; it is in my name that tribal homelands are being delivered into rapacious corporate hands; it is in my name that psychopaths are being given certificates of innocence; it is in my name that a paunchy policeman intrudes into the home of an “activist” and demands to know why she reads so many books! And it makes me sick.

Unchecked, the notion of “sovereign immunity” breeds a kind of moral indifference — not merely in citizens, but, crucially, in the civil servants, the policemen and others who administer the system of evil. Because, as Dickens noted in Little Dorrit — it is “nobody’s fault”. Terrible things get done, but no one actually does them! The passive voice is handy — things just get done.

Responsibility — response — is at the heart of it. Somebody must answer. Politicians, slow-moving beasts, are easy game. But politicians are still accountable, after a fashion, to their constituencies. It troubles me that my tax rupees make me complicit in the crimes committed by the state — or why am I paying a part of Nambi Narayanan’s compensation? But how much greater is the complicity of the people who man the apparatus — and yes, it is mainly men? The bureaucracy is, necessarily, complicit in the evil of an evil system. I am quite prepared to believe that the vast majority of civil servants are good people. But amongst them there must also be the people who are drafting the policies, fabricating the false cases, writing the orders, attending to the paperwork of hell. After all, who drafted the order that sent the quadriplegic G N Saibaba into prison? And the good people — my friends, often — who are not themselves perpetrators of evil, who have probably held their noses, but also their tongues, throughout their careers in “the service”, even these must at least have been witnesses to evil. So how come hardly anyone speaks up? Esprit de corps — or honour among thieves? Omerta? Or does sovereign immunity extend to their consciences as well?

Two important exceptions to the doctrine of sovereign immunity must be noted: The first of these is the Nuremberg principle. Developed in the context of the post-war Nazi trials, this clearly states that the fact that someone has been ordered to do evil things, albeit by a “sovereign”, confers no immunity, no moral or legal absolution. The second might be inferred from the “responsibility to protect” — “R2P” — doctrine that was developed in the context of the Rwandan genocide and the Serbian wars of the 1990s and formally adopted by the UN in 2005: Sovereign states that violate fundamental human rights forfeit their sovereign immunity, and become liable to forcible interdiction. The hypocrisy in the application of these doctrines is undeniable. But that does not take away from the force of their implicit insight into the question of sovereign immunity.

The writer taught at the Department of English, Delhi University

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

More From Alok Rai

- The native colonialV S Naipaul gave writers in once-colonised countries confidence. But he also exonerated colonialism...

- The soundtrack of democracySupreme Court order on Jantar Mantar frames an often-ignored reality: Protest is a part of polity and the inconvenience it causes an affirmation of our…

- Blame the hatGeneral Bipin Rawat has been far too eloquent on matters he ought to be quiet about. He did sound silly while elaborating on ways to…

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario