Gained in Translation: Speaking of Ram

If we take the versions of Valmiki, Kamban, Kritibas and Tulsi, then at least two of those narratives unambiguously mention Ram heartily enjoying dishes prepared from animal meat, and there is also some mention of Sita consuming fermented drinks.

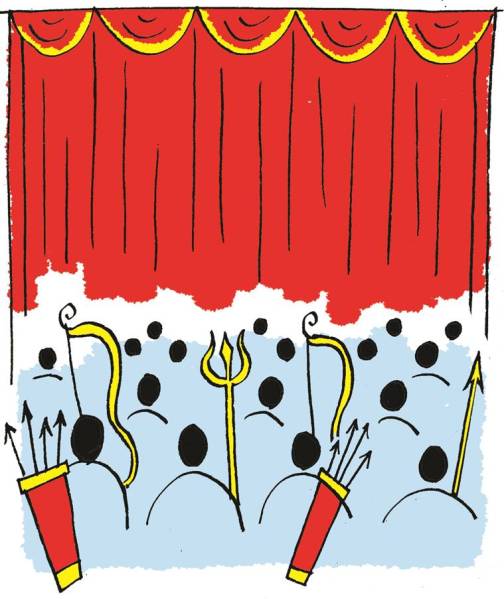

Illustration: C R Sasikumar

In Valmiki’s Ramayana, there is a description of a meat preparation on the banks of a river during the time that Ram, Sita and Lakshman spent in the forest while in banishment. While this description cannot be found in Tulsidas’s Ramayana, Valmiki’s version — often considered to be the first Ramayana — alludes to this quite clearly.

It is also clear that this meat was not that of chicken or goat. We can say this because there are unambiguous references to the meat of deer and pig, at least. While we do not know if Ram felt strongly towards cow, or if he ever exalted cow to the status of a mother, consuming cow in the forest does not seem like a bright idea either.

If we take the versions of Valmiki, Kamban, Kritibas and Tulsi, then at least two of those narratives unambiguously mention Ram heartily enjoying dishes prepared from animal meat, and there is also some mention of Sita consuming fermented drinks.

Now the question for a thespian such as myself is this: if I were to present a story of Ram on stage, could my Ram be shown consuming meat? And if he is shown eating meat, would I be risking my life as well as that of the said Ram on stage? Most plays in India are still based on the two grand epics — Ramayana and Mahabharat. If you are keen on producing something on stage which elicits questioning as well as enthusiasm, there can hardly be better stories waiting for you.

But what does a theatre professional do? Yes, you have Valmiki on your side, Kritibas too is on your side, so are 300 or so other Ramayanas. But this is also a country where a man, on a mere suspicion of consuming meat, is dragged to his death. Whatever life that was left in this man is sniffed out by the accompanying kicks of the police officials. In this country then, how far is theatre truly free?

It is said of my craft that when Saint Bharat’s 100 sons spoke in favour of the asuras (demons) in the presence of gods, Indra was so infuriated that he banished this art form from his heavenly abode. And thence came this craft to us mortals.

If you think about it, that myth might just be true. Where have you ever encountered a single imagination of heaven where you are enticed by grand performances of Girish Karnad’s Yayati, Dharamvir Bharti’s Andha Yug or Mohan Rakesh’s Lahron ke Rajhans in afterlife?

But then again, imagination is a theatre artist’s best friend. The problem isn’t when someone does not achieve anything; the problem is when someone does something. Take Ram again, for example. The man accomplished many things, but to make a play out of his rule is next to impossible. V D Savarkar is an easier proposition.

What is even more ironic is that the art of Ramlila is endangered. What happens if some people object to Sita letting her hair open in a certain theatrical depiction. After all, this is country where Ram has been imagined as being Muslim and Sita as a Sikh. Now what happens if someone in the audience sees a hidden Quran in Ram’s beard or a hidden kirpan in Sita’s sari? Then what does an artiste do?

It is obvious that in today’s Ramrajya, an artiste cannot speak of Ram freely but can invent lores of Savarkar freely. The problem is that the Ram we confront today is not that ideal mortal who was continuously reimagined by millions through their personal reflections. The travesty is that if Valmiki was around today, he would have seen his opus burn publicly, get no employment from the State and his life would have been in danger.

I often wonder about the Valmiki who resided in the forests. Would he have abandoned Ram to tell a story about Savarkar? Would his tale delete all references to Ram eating meat? Would he have feared for his life while penning such sacrilege? I think not.

That is not the Valmiki I imagine. Though I also imagine that this episode of men possibly commissioning plays on Savarkar — in the name of Ram — will be retold to us for years to come. I also imagine that these retellings will not exalt the men who acquiesced easily either. Theatre teaches us that history can be often cruel.

Translated from Hindi by Shatam Ray

Majumdar is a playwright and theatre director based out of Bangalore

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario