The curriculum taboo

Schools, colleges and other educational institutions desist from engaging with caste in the false hope that education will remove the social inequality.

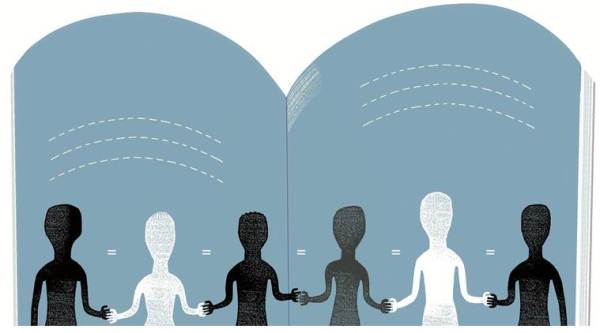

If you are part of the urban middle class, you learn to perceive caste as something remote even as it permeates your everyday world and gives you an identity. (Illustration: C R Sasikumar)

A news report from Maharashtra reminds us why we must keep on engaging with older issues and debates. Even as a brave new India forges ahead with smartphones and cities, caste remains a major force shaping social relations and politics. Three adolescent Dalit boys were brutally assaulted and paraded naked after they were caught having swum in a well forbidden for use by Dalits. The assault was recorded on a video.

Perpetrators of violence against members of oppressed groups document their act themselves, apparently to establish their brazenness. Perhaps, they also intend to warn others against transgressing traditionally-maintained boundaries of upper caste authority. They don’t believe that history has moved on, towards new social norms. There is something in the current political ethos that persuades them to hope for a return to old times.

The episode reminds me of the role that wells used to play in India’s social life before the advent of piped water. Wells were often demarcated as caste territories. To have a well of your own, in your courtyard, was a symbol of status. There were public wells too, commemorating the liberal vision of an enlightened authority figure. Several short stories by Premchand portray life around a well and the conflict that wells often witnessed. One poignant example is the story Thakur ka Kuan (The Thakur’s Well) probably written in the early 1930s. The plot is brief and the end bleak, although violent horror is avoided. An untouchable labourer’s wife makes an attempt to fetch water from a Thakur’s well. It is dark, and her husband is very ill and thirsty. The well accessible to the untouchables smells rotten because an animal has fallen in it. The labourer’s wife knows the terrible risk she is taking, but she goes ahead. Just when she is close to success, she is spotted and runs for her life. When she reaches home, she finds her sick husband drinking the foul water.

Many would like to believe that the portrait of India this story offers is obsolete. The Maharashtra incident proves that this is not entirely so. We can debate the exact nature of its relevance, but we can’t doubt it. As Premchand’s story figures in school and college textbooks in many parts of India, you can hear audio and video lessons on it on the internet. In most of these lessons, students are told to appreciate Premchand’s masterly treatment of old social problems like untouchability and superstition. Understanding and appreciation of his craft of fiction is important for getting good marks. The audio teacher insists that social problems like caste discrimination are a thing of the past. If they sometimes manifest today, it is only in remote villages. As expected, the lesson has a moral agenda, to establish that education is fighting against such inhuman practices.

Apart from including such literature in textbooks, education in most states does precious little to deal with caste issues in any depth or detail. Indeed, caste remains a curricular taboo: It is not supposed to be discussed directly. Nor is it acknowledged as a major social institution, shaping relationships as important as marriage. Not just schools and colleges, teacher training institutions also avoid engaging with it. All that is discussed is the reservation policy and its Constitutional aim. The hope that caste prejudices will gradually diminish, if not vanish, is based on general faith in education, rather than on any insight into how education works or how its agency can be deployed on a subject like caste.

If we try to answer two questions on this subject, we might achieve some clarity. The first question is: “Has education helped to speed up economic and social mobility among the lower-placed castes?” The second question is: “Has education helped to reduce caste-based prejudice?” The answer to the first question is, yes. On the second question, one can at best say: “Maybe, but not much”. Proof of this second answer can be found in many university campuses. From friendships to politics, the influence of caste can be observed everywhere. Many young people feel undisturbed by it. The rhetoric of being fair, open and unprejudiced is well-established in colleges, but no real learning about caste-based practices takes place. The belief persists that including the caste system in the curriculum will only reinforce it. Many schools and colleges are established by caste associations, and they too prefer to let the magic of caste remain subtle, percolating into the young mind quietly. The same applies to teacher training institutes. You cannot persuade people to take the time to read a book as slim as Indian Society (National Book Trust), written by the late S C Dube to promote informed dialogue about the caste system. Wild ideas and stereotypes nicely co-exist and flourish with revivalist politics which forbids any reference to caste on the ground that it will spoil the country’s image.

B R Ambedkar was right in seeing caste as a barrier to India’s intellectual growth, apart from being the lever of oppression. His teacher at Columbia, the educational philosopher John Dewey, had given communication a central place in his model of democracy. Ambedkar used the metaphor of social endosmosis to explain how the caste system prevents the flow of ideas and knowledge. Endosmosis ensures the passage of fluid through a membrane to an adjoining cell. The caste system, Ambedkar felt, deprives India of this basic means of social health. Like Dewey, Ambedkar had faith in the power of education to nourish democracy. Our system of education continues to be too weak to promote any kind of endosmosis, even across disciplines, let alone social groups. Someone studying science, engineering or management may never be intellectually challenged for holding casteist views. In routine life, such views reassure colleagues that you are normal. If you are part of the urban middle class, you learn to perceive caste as something remote even as it permeates your everyday world and gives you an identity.

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

More From Krishna Kumar

- Girl On The CoverWhy a photo of a Pakistani girl on a booklet in Bihar need not embarrass officials ..

- No room for questionsWhen spiritual leaders fall from grace, schools founded by them lack the acumen, ability to help students come to terms with the situation...

- Should we have defended Sanjay Leela Bhansali?Liberals must question themselves. There is nothing liberal about portraying women jumping into fire in a manner that doesn’t cause revulsion...

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario