|MercatorNet|December 4, 2017|MercatorNet|

Persuasion: Jane Austen’s greatest novel turns 200

The most moving love story she ever told.

When I was asked a few years ago if I would like to edit one of Jane Austen’s novels, I quickly answered that I would be happy to, and especially if I could edit her greatest novel.

“I’m sorry, Rob,” was the reply. “Someone is already editing Pride and Prejudice.”

“That’s ok,” I said, much relieved. “Pride and Prejudice is not Austen’s greatest novel. Jane Austen’s greatest novel is Persuasion.”

It is – among many other things – the most moving love story she ever told. Anne Elliot is the second daughter of the absurdly vain baronet Sir Walter Elliot of Kellynch Hall. Frederick Wentworth is an officer in the British navy during the Napoleonic Wars.

Eight years before the novel begins, Wentworth proposes to Anne and she accepts him after a brief and intense courtship, only to be persuaded by her father and her older friend Lady Russell to break off the engagement. Wentworth, angry and badly hurt, goes back to sea, where he conducts a successful series of raiding expeditions on enemy ships, and amasses a fortune in prize money.

When Napoleon abdicates for the first time in April 1814, Wentworth returns to England and soon pays a visit to his sister, who now lives near Anne. Throughout his absence, meanwhile, Anne has found no one who compares to him, and has pined away to the point where now, at 27 years old, her bloom is gone and she has begun the descent into spinsterhood.

Many critics have argued that, as a result of suffering and regret, Anne is already “mature” when the novel opens, while the rich and carefree Wentworth has a good deal of growing up to do before he recognizes – or, rather, re-recognizes – her worth.

On the contrary, for all that divides them when he returns, Anne has as much to learn about love as Wentworth does, and her journey toward their reconciliation contains as much confusion as his. Indeed, part of the enormous appeal of Persuasion is Austen’s ability to convey the ways in which Wentworth and Anne are moving steadily toward one another even as their various missteps, flirtations and assumptions seem to be driving them still further apart.

Their reunion is the finest scene in all of Austen, and in it they do not even speak face to face, for Austen understood that mediated and misdirected messages frequently carry a far greater charge than explicit declarations.

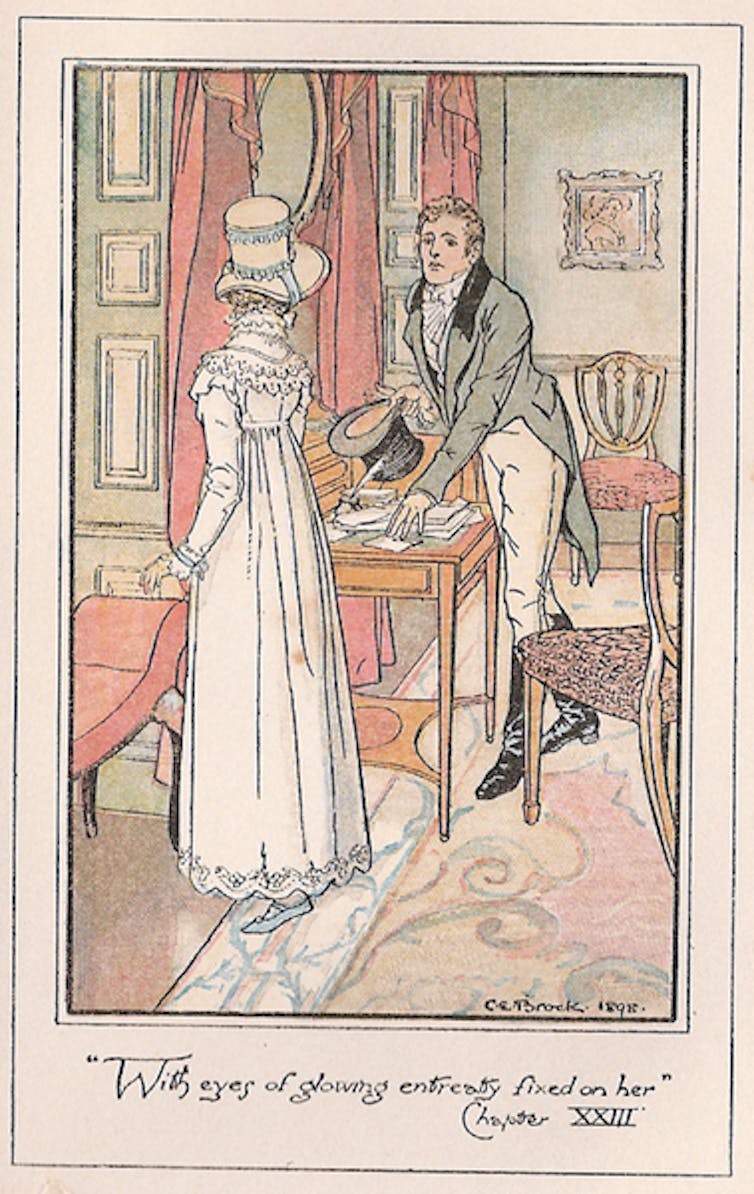

Anne and Wentworth are both in a room at the White Hart Inn in Bath. He is sitting at a desk writing a letter. She is nearby speaking to a mutual friend, Captain Harville, about men, women and constancy.

Harville believes that men feel more deeply than women. Anne takes the opposite view, and while she does not mention Wentworth or her own circumstances, everything she says is clearly with him in mind.

She has spoken to no one about her grief over Wentworth, and it is not long before eight years of pent-up anguish flood out of her. “We certainly do not forget you, so soon as you forget us,” she tells Harville. “It is, perhaps, our fate rather than our merit. We cannot help ourselves. We live at home, quiet, confined, and our feelings prey upon us.”

Wentworth, still writing his letter, overhears Anne’s comments and knows immediately that she is speaking about their relationship, and about all that has been lost.

Seizing another sheet of paper, he begins a second letter in which he records his feelings toward her as she utters hers toward him, and which he leaves behind on the desk for her to read.

Ralph Waldo Emerson objected to Austen’s novels because he found them “imprisoned in the wretched conventions of English society, without genius, wit, or knowledge of the world.”

But Austen knew that love is the very largest concern of life, then as now, and in Persuasion she makes Anne’s whole world hang on a single letter. It is a moment that demonstrates both the superb compression and the enduring appeal of her art.

If Wentworth loves Anne, she has a future that stretches as far as the seas. If he does not, she has only a past that will increasingly consume her. She reads the letter. He does love her. Her joy is inexpressible. So is ours.

What’s more, Austen has contrived to tell both Anne and the reader at the same time, and her passionate affirmation of personal preference and individual desire far transcends the “wretched conventions of English society.”

“You pierce my soul,” Wentworth’s letter reads. “I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone for ever. I offer myself to you again with a heart even more your own, than when you almost broke it eight years and a half ago.” Anne is overwhelmed.

During the novel she has been transformed, from faded to blooming, from nobody to somebody, from “only Anne” within her family to Wentworth’s “only Anne.”

Persuasion is Austen’s last published work. She began it when she was nearly 40 years old, and when she finished it she was within a year of her death. Perhaps not surprisingly, it is one of her shortest – and it is certainly her saddest – novel.

But it is also her subtlest and most impassioned. “After a long immersion in [Austen’s] work,” British novelist Martin Amis writes, “I find that her thought rhythms entirely invade my own.”

Robert Morrison, Professor of English Language and Literature, Queen's University, Ontario

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

December 4, 2017

Oh joy! Another Jane Austen anniversary! This time it’s to mark the publication of her novel, Persuasion, 200 years ago (and six months after the author’s death at the age of 41). I have not read the book (an omission to be remedied) but have seen the 1995 film made by the BBC in partnership with two companies, American and French.

Without having seen other versions I found this portrayal of a heroine who, seemingly doomed to spinsterhood, gets a second chance at love, convincing and very satisfying. Canadian literature professor Robert Morrison considers Persuasion (the book) "the most moving love story" Austen ever told. His article is a particularly nice piece of Austen appreciation.

In Australia, where a bill to legalise same-sex marriage will soon be passed, Presbyterian pastor Campbell Markham explains why he will be relinquishing his status as a marriage celebrant. His is a powerful protest against the subversion of marriage.

Without having seen other versions I found this portrayal of a heroine who, seemingly doomed to spinsterhood, gets a second chance at love, convincing and very satisfying. Canadian literature professor Robert Morrison considers Persuasion (the book) "the most moving love story" Austen ever told. His article is a particularly nice piece of Austen appreciation.

In Australia, where a bill to legalise same-sex marriage will soon be passed, Presbyterian pastor Campbell Markham explains why he will be relinquishing his status as a marriage celebrant. His is a powerful protest against the subversion of marriage.

Carolyn Moynihan

Carolyn MoynihanDeputy Editor,

MERCATORNET

Persuasion: Jane Austen’s greatest novel turns 200

By Robert Morrison

The most moving love story she ever told.

Read the full article

Read the full article

From cops on the beat to spycams and algorithms

By Karl D. Stephan

17,000 different policing authorities is better than one big one.

Read the full article

Read the full article

How one pastor is responding to Australia’s redefinition of marriage

By Campbell Markham

A Presbyterian pastor explains why he is relinquishing his status as a marriage celebrant

Read the full article

Read the full article

The new importance of children in America

By Shannon Roberts

Why is sex going out of fashion?

Read the full article

Read the full article

Same-sex marriage and the service-provider state

By Zac Alstin

Autonomy and authenticity are trending.

Read the full article

Read the full article

A weird tactic to promote abortion backfires in Ireland

By Carolyn Moynihan

‘Not in my name,’ say former Tuam babies.

Read the full article

Read the full article

What Tocqueville prescribes for the crazy American soul

By Ryan Shinkel

The Art of Being Free.

Read the full article

Read the full article

These groups support gay marriage while backing a cake baker’s first amendment rights

By Elizabeth Slatteryand Kaitlyn Finley

A US Supreme Court case is critical for free expression.

Read the full article

Read the full article

MERCATORNET | New Media Foundation

Suite 12A, Level 2, 5 George Street | North Strathfield NSW 2137 | AU | +61 2 8005 8605

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario