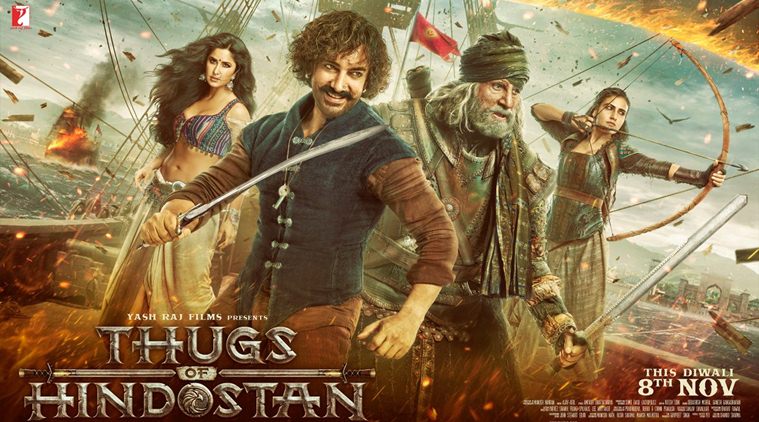

Thugs On The Silver Screen

‘Thugs of Hindostan’ is a satirical challenge to dominant nationalist narratives

Thugs of Hindostan released on November 8.

Critics have ranked Thugs of Hindostan as one of the worst high-budget films in Hindi cinema. The film gives several opportunities to the critics to be ruthless: A predictable storyline, pinheaded characters, ear-splitting music and mediocre visual effects. However, an aspect of the film does merit attention. The choice of characters, locations and certain symbols have deep political meaning that connect the film with contemporary political situations. Subtly, the film depicts a robust anti-establishment fervour, which may not go down well with the current ruling elites.

It is unquestioningly accepted that the makers of modern Indian history are mostly upper caste, educated elites or belonged to the feudal warrior castes. There may be exceptions like Birsa Munda and Babasaheb Ambedkar in this galaxy, but Bollywood mostly narrates the stories of social elites, their extraordinary heroism and their nationalist commitments. When it comes to patriotic films like Kranti, Gadar, Lagaan etc, there is very little space for Dalit or Adivasi imagery. The caste question is often invisible and even when Dalit characters appear on screen, they are often stereotypical.

Thugs of Hindostan is a period fantasy in the populist patriotism genre. The main characters are bandits, a conman and a sex worker. Dalits, Adivasis and underprivileged women have historically been marginalised and suppressed. However, their histories have not found much space in Bollywood. In the contemporary times of “Islamic terrorism”, Muslims are also categorically attacked as enemies of the Hindu nation-state. Within the Hindutva nationalist circles, these groups are often attacked for being particularistic and narrow and, therefore, removed from the nationalist objectives. The “thugs”, “mavalis” or “haramis” are negative stereotypes, often crafted by the colonial elites, to segregate and belittle certain sections as “criminal castes and tribes”. The poor castes, outlaws and stateless people were often seen as a threat to early colonial rule.

The main protagonist, Firangi Mallah, is introduced as an “anti-national” villain who later mutates into a patriotic figure. He is a low-born, immoral and petty conman. His character stands in opposition to popular nationalist figures (like Mangal Pandey) that led the struggle against the British with valour, steeped in ethical values. Interestingly, Firangi’s low-caste social location or even his criminal past does not prevent him from performing heroic deeds to liberate the land from the East India Company.

The second lead character is Khudabaksh, an elderly Muslim fugitive. Importantly, he is presented as the greatest patriotic figure. He is the leader of the bandits that steals government’s shipments and aspires to liberate the region from the British yoke. Then there is the young burkha-less warrior, Zafira, the forgotten heir of a benevolent king whose father is unceremoniously killed by the cruel British general, John Clive. Her character subverts the conventional meaning of the subjugated Muslim woman.

The three protagonists are criminals and outlaws but are moved by moral, nationalist convictions. The militant comrades of the rebels are not trained warriors but mostly appear as average tribal folk living in an unknown jungle. Further, a sex worker Surraiya, helps the rebels to strategise the battle against Clive. Creating nationalist cinema with such characters is a daring attempt. Thugs of Hindostan thus brings the peripheral, the lumpen proletariat and other degraded groups centrestage in building the foundations of the new nation. It gives the film a subaltern-satirical Dalit perspective.

In one scene, the rebels hide in an effigy of Ravana that is supposed to be set on fire by Clive. The rebels burst out of the Ravana effigy and burn the general alive. This is a radical metaphor. In Kabali, too, tales from the Ramayana were subverted to represent Ravana as a symbol of the poor and the rebellious. Within Dalit-Bahujan folklore, Ravana is not just a demon king but he also possesses moral character.

Interestingly, there are “Azadi” slogans all around, in the midst of dance, alcohol and revolutionary sermons. It reminds the audience about the crisis that the “anti-national JNU” witnessed two years ago. There is also a red flag floating on a citadel. At a time of Hindutva’s cultural hegemony, Thugs of Hindostan looks like a satirical challenge to the nationalist imagination of the past.

The writer teaches at the Centre for Political Studies, JNU

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

More From Harish Wankhede

- Return to a radical pastBhima-Koregaon protests reflected acts that define Dalit consciousness and its agenda ..

- A New Dalit Hero‘Newton’ showcases a protagonist unencumbered by his past..

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario