The missing 4,007,707

Can a democracy permit so many to be in a state of liminal legality? NRC poses a political and moral question

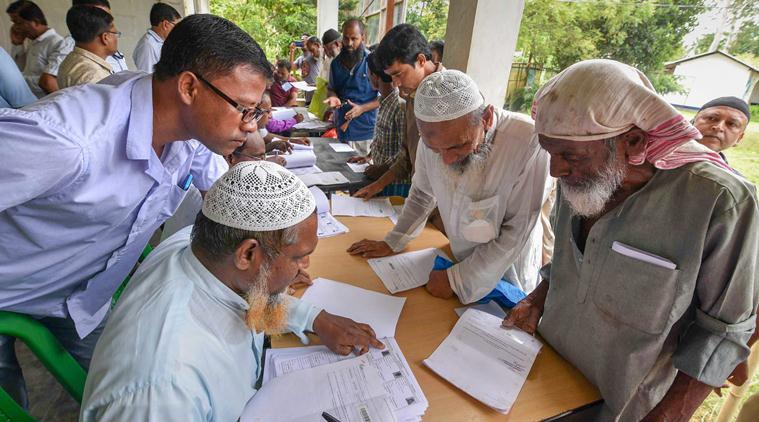

The first draft was published on December 31, 2017, and the names of 1.9 crore of the 3.29 crore applicants were incorporated. (PTI)

The possibility — whether immediate or somewhat remote — that at the end of the process as many as 4 million people may lose their legal status as citizens should not be a cause of celebration in a democracy. Nor should it generate a mad rush among politicians competing for political credit.

If anyone can claim credit for the completion of the draft NRC, it is the coalition of regional political forces in Assam — notably the AASU and the AGP — for relentlessly pushing for it since the days of the Assam Movement. Their decision to turn to the judiciary can only be seen as a positive step. In Assam, there has been much praise for the coordinator of the NRC, Prateek Hajela, and his staff for successfully and competently bringing this enormously complex exercise to near completion.

Hajela’s observations are the best argument I have seen in favour of the NRC. When a reporter asked him about the implications of Bangladesh not being on board, he replied, “It is not really my charter.” As an administrator, he believes his job is to implement actually existing laws. Since the number of unauthorised immigrants in Assam has long been a matter of speculation, he considers finding out the actual number to be an important public service. “Once we are sure what we have in hand, a policy will be made.” But it will be naïve to think that the NRC will finally settle Assam’s tangled “foreigner” question. The issues that Hajela rightly considers to be beyond his mandate will ultimately be decisive.

In the contemporary global system, no state can act on illegal immigration unilaterally. Just because one state decides that a person is a citizen of another country, the other country is not obligated to accept that determination. One way in which governments act on deportation is to sign bilateral agreements for the readmission of nationals of the relevant country. Not only is there no such agreement between India and Bangladesh, by all indications India has never approached the subject of deportation with Bangladesh.

There is enough indication that the ruling party would have preferred to pass the Citizenship Amendment Bill, 2016 before the completion of the NRC. But in Assam the bill was seen as deliberately muddling the situation. If Hindu unauthorised migrants from Bangladesh — including those who have come recently — have a path to Indian citizenship, their exclusion from the NRC becomes a matter of no consequence.

The shelving of the bill has given the ruling party a temporary reprieve. But it will probably be re-introduced in Parliament in some form in the near future. If the proposed amendment becomes law, the impact on the actual meaning of the NRC will be huge. While Hindus who are found to be ineligible for inclusion in the NRC will no longer be considered illegal immigrants, the rest of the people excluded from the NRC will remain in a state of “permanent temporariness.”

It is hard not to see the shelved citizenship amendment bill as one that would effectively introduce into Indian citizenship law a distinction between non-Muslim and Muslim immigrants crossing the Partition’s borders. In the eyes of many in the ruling party establishment, this is an unfinished piece of Partition business.

The Supreme Court has been a key player in the NRC exercise. Not only has the two-judge Supreme Court bench closely supervised and monitored the process, it has weighed in on a number of related issues. For instance, the original ruling directed the Indian government to complete the fencing of the border and to maintain “vigil along the riverine boundary… by continuous patrolling.” It had also directed the government to develop, in consultation with the government of Bangladesh, appropriate mechanisms and procedures for deporting those declared illegal migrants.

Significantly, the Supreme Court bench appears to have given the least attention to this part of its original direction. The NRC is now nearly complete without any progress on this part of the process. The judicialisation of matters that are ultimately political is always a mixed blessing. It raises unusually high expectations. But courts cannot deliver political miracles. Only a naïve legalist would expect the Supreme Court to magically settle Assam’s vexed foreigner question — a profoundly political question that is ultimately about the birth of the republic itself.

The public interest will be best served if our politicians now move to end the game of taking credit and assigning blame. The Supreme Court bench said on Tuesday that the complete draft NRC could not be the basis of any coercive action against anyone. The home minister has also given that assurance. But words are unlikely to give confidence to people whose names are not included.

Citizenship is “the right to have rights.” Not to be included in the NRC is serious business. We are in uncharted territory.

I would like to read the silence on the question of deportation — in the diplomatic arena as well as in the Supreme Court’s otherwise proactive agenda — as a positive sign. Perhaps deportation is not what anyone in authority has in mind. Even in that case, can a democracy permit 4 million people to be in a state of “liminal legality”?

In certain circles, there has been talk of giving work permits to those not included in the NRC. But a work-permit regime functions on the premise that the person has full rights of citizenship in another country. Giving work permits to people that India would like to expel but can’t because Bangladesh does not accept them as citizens, is not really a work-permit regime. It only creates a group of right-less people who can work but cannot claim any other rights in India or anywhere else.

Moving forward, we should not rule out amnesty. Surely, if we were considering giving citizenship to minorities on humanitarian grounds, it is not that much of a leap to consider that we expand our moral horizon and extend the humanitarian umbrella to others as well.

The writer is professor of political studies, Bard College, New York

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

More From Sanjib Baruah

- A lesson from Arunachal PradeshDebate over the state’s anti-conversion law points to the need to give more attention to religious change from the perspective of the ‘converted’...

- Citizens, non-citizens, minoritiesUpdating of the National Register of Citizens in Assam and the Citizenship Amendment Bill could lead to a redrawing of the demographic map of South…

- Stateless in AssamThousands could be declared non-citizens when the National Register of Citizens is finalised. Since their deportation is an almost impossible option, the focus will be…

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario