The Belfast solution

Peace process in Northern Ireland could offer a roadmap for Kashmir.

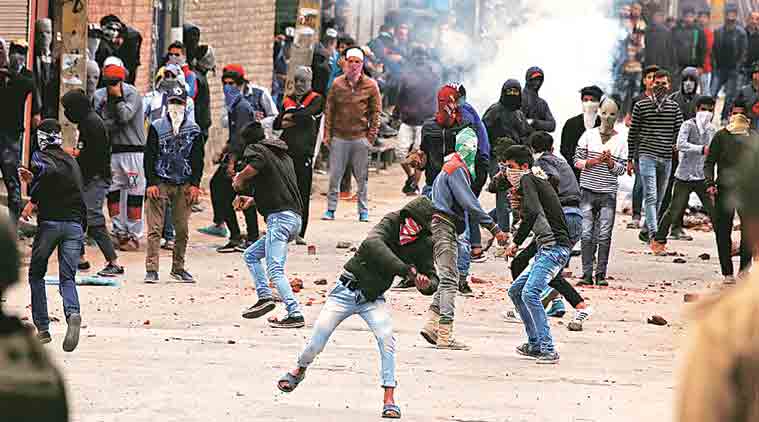

A close look at the history of separatist movements shows that the crux of the problem is not so much the gain of territorial control but the acknowledgement of hurt, anger, betrayal and the loss of prestige of a people. (Representational Image)

On the day President’s rule was imposed in Kashmir recently, I was visiting Belfast. I was taking the Black Taxi Tour. I was being driven by an ex-IRA (Irish Republic Army) soldier who was taking me on a visceral tour of perhaps of what used to be some of the most violent streets in the world. A whistle stop tour of Shankill Road, Falls Road and Sandy Row was instructive. The violence of a centuries-old conflict between Protestant and Catholic communities was over. But the scars of past events, like Bloody Sunday or the tragic hunger strike of Bobby Sands, were too deep and raw to be forgotten or filled. Which is fine for the people of Northern Ireland as long as peace rules the streets.

The moot question, therefore, is: If the Irish could achieve peace what bedevils Kashmir? The sceptic is entitled to ask — what’s the connection between the two conflict zones? The similarities between the conflict in Northern Ireland and Kashmir are surprising but real. We cannot turn our eyes away from the reality that a religious divide has emerged in Kashmir. The idealism of Kashmiriyat now sounds like a fable once told. On ground zero, Kashmiri Hindus have been forced to leave their homeland. The strands of a Wahabi-inspired Islamic counter-culture is making inroads in the Valley. In Thatcherite Britain, religious polarisation in Northern Ireland was also at its peak. The world would wake up every day to images of British army soldiers patrolling the inner streets of Belfast. Paramilitaries on both sides of the Protestant-Catholic divide would be in action, sniping, maiming, torturing and killing innocents.

Replace those images of the past with those of stone pelters attacking troops in the Valley, search-and-cordon operations, terrorists ambushing convoys and raiding security camps. Then take a look at the compulsions and behaviour of career politicians in both areas. For historical reasons, just about every politician in the Valley chooses from the shade card of autonomy to separatism. It was a similar deck with the Sinn Fein and other separatist organisations when they began negotiations with the British government about Northern Island’s future.

Yet, despite all the contradictions, peace has held in Northern Ireland for the last 25 years. Northern Ireland is still part of the UK. The Good Friday Agreement, which ushered in peace, by and large still holds.

The two mechanisms that restored peace in Northern Island, in my view, were the emergence of honest but wily brokers who understood the contradictions of the difficult process, yet, successfully guided the peace negotiations. This went hand in hand with the effective addressing of the grievances of the affected citizenry.

So, who could be our answer to President Bill Clinton and British Prime Minister Tony Blair — the two men who brokered the Good Friday Peace agreement. The answer is blowing in the wind. It can’t be an international negotiator because that would be unacceptable to any government at the Centre. It would have to be a personality respected by all sides — which means the Hurriyat’s would have to be persuaded to come into the fold. This might sound like a contradiction, knowing the Hurriyat separatist agenda, but we must remember that organisations like Sinn Fein had similar agendas. In their case, the promise of “peace with honour” whittled their hardened stance and persuaded them to stay within the Union in return for equal representation.

Therein lies the key to the problem: “Peace with honour”. There are too many vested political and subversive interests at play in Kashmir for such a lofty aspiration to work on the ground. But, then this is the job of the honest yet wily broker/negotiator.

A close look at the history of separatist movements shows that the crux of the problem is not so much the gain of territorial control but the acknowledgement of hurt, anger, betrayal and the loss of prestige of a people. It does not take a wild imagination to understand that Kashmiris, be it Muslims or Hindus, have been emotionally brutalised. The negotiator has not only to work out the deal but offer a salve to close these open wounds.

The joker in the pack is, of course, Pakistan and the insidious role it can play in the process. The Hurriyat might insist on Pakistan’s involvement in these negotiations but I suspect that the Hurriyat’s hard-line stance is in response to governments in Delhi, which treat it with utter contempt. There is no reason why the Hurriyat and other quasi-separatist forces cannot see reason and discard its Pakistan card if they sense that real change is around the corner.

In Belfast, “Black taxis” conduct tours and keep the legend of the likes of Bobby Sands alive. The inside streets flutter with loyalist and united Ireland flags. But the guns have disappeared. The anger and hurt of the people is channelled in a kind of touristy remembrance of the “troubles”. Kashmir is also welcome to its own version of the Black taxi tour. That can happen after the guns fall silent.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario