Delhi and Canberra, a lost chance

Shelving of the Varghese report does not speak well of Australia’s desire to improve people-to-people ties with India.

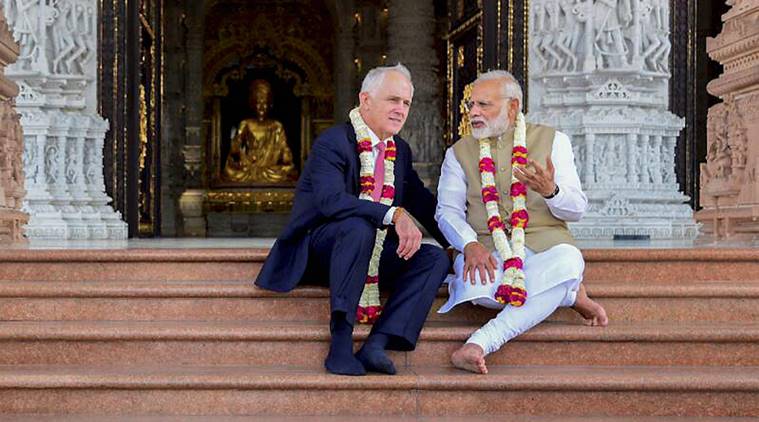

The geopolitical congruence flows from three factors: Both countries are faced with the “sharpening ambition of China to become the predominant power in the region”. (Photo: PTI)

On July 12, one of the most significant documents on Australia’s ties with India was released in Canberra. More than 500 pages long, the report, ‘An India Economic Strategy to 2035: Navigating from Potential to Delivery’ by one of Australia’s most formidable strategic experts, Peter Varghese (former High Commissioner to New Delhi and Secretary Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and currently Chancellor of the University of Queensland) is a magnum opus even by the author’s exacting standards. The report will be released in Delhi, next week. Its recommendations could potentially transform bilateral ties in a manner reminiscent of Australia’s ties with Northeast Asia after the release of the economist Ross Garnaut’s report in 1989.

Yet, the report has, in the words of Angus Grigg of the Australian Financial Review, been given a burial by the Australian Federal Government. Last April, Prime Minister Malcom Turnbull, on a visit to India, commissioned the report with a splash. This July, the Australian Trade and Investment Minister Steve Ciobo released it with little fanfare, and without even a media briefing or a press conference. In substance, the report is extraordinarily detailed, with incisive economic analysis provided by McKinsey & Company, and brilliant in its recommendations. In the interests of full disclosure, I was part of the India Reference Group that Varghese consulted, which included Rajiv Kumar, Montek Singh Ahuluwalia, Shyam Saran and Sanjaya Baru.

What has gone wrong? Can the report’s recommendations still be rescued from the naysayers in Canberra? By most accounts, it is Varghese’s candour about China that is making Canberra nervous. The report is not about China or its potentially hegemonic designs over the region. It is primarily about economics. But as a former head of the Office of National Assessment, Varghese argues correctly that a long-term economic strategy towards India should rest also on two other critical pillars that support the relationship. People-to-people ties and geopolitical congruence.

The geopolitical congruence flows from three factors: Both countries are faced with the “sharpening ambition of China to become the predominant power in the region”. Both Australia and India support a rules-based international system because Australia (and indeed India) can neither “buy or bully” its way in the world (clearly only a slightly veiled reference to China). Finally, India ‘s desire to build inclusive regional institutions must be encouraged as should its willingness to work closely with the other great democracies in the region, Australia, Japan and the US.

All this is argued by Varghese with the underlying recognition that India will not surrender its strategic autonomy and it will seek to preserve maximum freedom of action. But Varghese recommends (which few in India would question) a strategic equilibrium that accepts China’s growing weight and yet underscores the importance that democracies attach to a rules-based order. This is common sense — realpolitik, rather no machtpolitik. But it seems, if the quiet burial of the report is good evidence,that the current political and bureaucratic leadership in Canberra is back to articulating a China policy reminiscent more of Chamberlain rather than Churchill.

In any case, geopolitics forms a small section of the tome. The real substance is in the 90 recommendations in some key sectors where Australia has a comparative advantage that could ensure that India is amongst the top three of Australia’s markets by 2035, and the third-largest recipient of Australian outward investment. These sectors are resources and mining, agribusiness, tourism, energy, health, infrastructure, financial services, sports, science and innovation, defence and security, and education.

A strong and productive relationship in the education sector, from teaching in schools to cutting-edge research in universities, could be a game changer. This is endorsed by Varghese, who argues that Australia’s “growth and prosperity” will be driven by its ability to attract the “best and brightest” from India. And that Australia could help India realise the vast potential of its demographic dividend and Australian education service providers, across sectors, need to collaborate more and compete less in a market that can accommodate them all. It can only be hoped that Australian universities take this recommendation seriously at a time when the Chinese student market is becoming increasingly volatile.

But a more serious concern is that the report will become just another marker in a familiar track of lost opportunities that have defined New Delhi’s relations with Canberra. For some years now, it has been evident that India’s relationship with Australia is an idea whose time has come. There are, in fact, few countries that share such convergence of values and interests. And yet, the relationship has yet to live up to its potential.

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi arrived in Melbourne on November 2014, he was the first Indian PM to visit the city for a bilateral visit since Indira Gandhi. Unlike Indira Gandhi’s visit, which is remembered today for its insignificance, Modi’s Australian yatra promised to be the most important ever made by an Indian PM for relations between the two countries.

The Governor hosted a chief executives’ round table — I chaired it — at which Modi had the opportunity to interact with the who’s who of Australian business. Later, he addressed more than 500 business leaders. There was an unprecedented new warmth in bilateral relations. It is time for the political leadership in New Delhi and Canberra to take charge once again before the relationship descends into frosty weather. The first step would be to resurrect the Varghese report and commission a reciprocal report that reflects New Delhi’s view of the relationship.

The writer is founding director of the Australia-India Institute and professor of International Relations at JNU.

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

More From Amitabh Mattoo

- A history of undemocracyThe fall of the Mehbooba Mufti government is only the latest instance. New Delhi’s policy towards Jammu and Kashmir has been to prefer rule by…

- A vision for reconciliationA reminder on his first death anniversary: Mufti Sayeed’s politics celebrated democracy, diversity..

- Masked men of KishtwarThe anger of a lost generation threatens the idea of J&K..

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario