CRISIS IN CATALONIA

“Calling these people political prisoners shows a lack of respect”

Ex-communist leaders tortured under Franco criticize comparisons with today’s jailed Catalan officials

Madrid

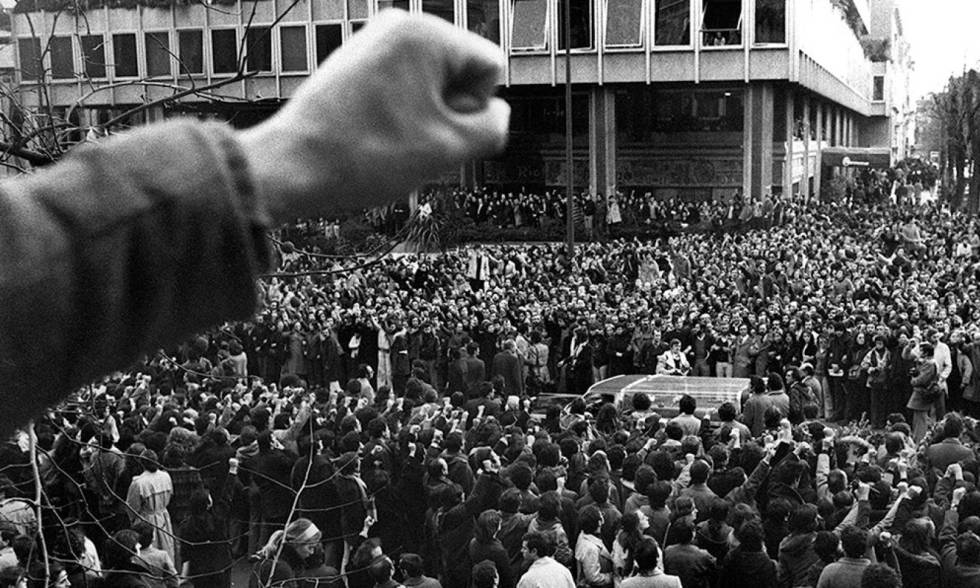

Political prisoners Víctor Díaz and Raúl Herrero. ULY MARTÍN

“I was a prisoner for eight years in Madrid, Calatayud, Soria and Segovia because of my political ideas, and I don’t even know how long I lived in hiding,” recalls Víctor Díaz-Cardiel, 82. “At the General Directorate for Security in Puerta del Sol you’d get beaten up by seven or eight people until you collapsed. My father was beaten so he wouldn’t engage with any more communist militants… And now they tell me that the Jordis [Sànchez and Cuixart, leaders of Catalan civic groups ANC and Òmnium, currently in pre-trial custody] and jailed members of the Catalan government are political prisoners? To trivialize reality like that is a lack of respect.”

This veteran leader of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) – a group banned under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco and only legalized two years after his death in 1977 – was elected to the Central Committee in 1965, during his first stint in prison, and later he served as secretary general in Madrid. Díaz-Cardiel disagrees with the decision by a judge at the Audiencia Nacional, Spain’s High Court, to place former members of the Catalan government in pre-trial custodyon charges of rebellion and sedition. He calls the move “a mistake” and “politically disproportionate.”

You could be held there indefinitely, because we were in a state of exception. There were no limits

CARLES VALLEJO

Yet he views it as an insult to have them described as political prisoners, as Catalan separatists and the left-wing anti-austerity party Podemos are doing.

“They are politicians in prison, not political prisoners,” adds Raúl Herrero, a member of the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE) and a former PCE leader in Madrid.

Herrero was arrested in 1970 for being “a dangerous communist,” as his police file attests. He was granted conditional release a year later, after spending six months at a penitentiary hospital to recover from the torture he was subjected to. He would rather not talk about that, and instead focuses on Dolores González Ruiz, a lawyer who was instrumental in his release, and who was herself seriously injured as a result of a far-right attack against a Madrid law firm in 1977, known as the Atocha Massacre.

“It is debatable whether you could legally talk about rebellion [by former Catalan officials], but don’t talk about repression to those of us who have mobility problems due to beatings inside Francoist police stations,” says Herrero. “I’m not the emotional type, but what’s going on today has nothing to do with those days.”

“The Jordis and Catalan government members are being unfairly detained, but you can’t just casually call them political prisoners, because you would be drawing false parallels between democracy and fascism or dictatorship. We cannot do that – especially for the sake of the new generations,” agrees Carles Vallejo, 67, who is president of the Catalan Association of Former Political Prisoners under Franco.

Vallejo was sent to Madrid’s Cárcel Modelo twice: once in 1970, for organizing the Comisiones Obreras (CC OO) union at a well-known auto factory. “Later I was forced to go into exile because the prosecutor was asking for 20 years behind bars for crimes that are no longer considered as such. Each situation should be looked at in context. Fascism is complete arbitrariness. You cannot draw these comparisons.”

They are politicians in prison, not political prisoners

RAÚL HERRERO

The torture sessions were “a horrible nightmare,” he recalls. The punches, the kicks, the interrogation sessions every two hours, the lack of personal hygiene, the solitary confinement that made him lose all sense of day and night… It was 20 days of hell inside the Political-Social Brigade headquarters. “They threatened me with a gun, but the worst part was the uncertainty,” he remembers. “You could be held there indefinitely, because we were in a state of exception. There were no limits.”

“To say that there are political prisoners in Spain is to falsify history, and it is hypocritical as well,” says Antonio Gallifa, another former PCE leader, in angry tones. He got a four-year sentence for presiding a clandestine assembly of CC OO delegates in an abandoned factory, was sent to Carabanchel prison, and was subjected to torture like the others.

“After nearly a month that was not exactly pleasant, I still hadn’t given them a single piece of information,” notes Gallifa proudly. “I confessed to nothing.”

This victim of Francoist persecution believes that the people behind the unconstitutional independence push in Catalonia are “criminals” who have committed “one unlawful act after another.”

English version by Susana Urra.

HAS SPAIN REALLY REGRESSED TO THE 1970S?

N. C. / K. L.

According to the The Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index, Spain is a full democracy, with a score of 8.3 out of 10 in 2016.

Meanwhile, Amnesty International says there are no political prisoners in Spain – although the organization prefers the term prisoners of conscience, arguing that the term “political prisoner” is not defined under international law and is therefore open to interpretation.

“In the case of the Catalan leaders and politicians we don’t consider them prisoners of conscience because they have been jailed accused of the crime of sedition. We do believe, however, that the charges are exaggerated and we ask for them to be freed, but we don’t consider them prisoners of conscience,” explains Amnesty International spokesperson Ángel Gonzalo.

According to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, a detainee is only a political prisoner when that detention is purely political without any connection to codified crime.

With Spanish democracy and the separation of powers recognized by all the principal international organizations, it is worth asking if we are less free. It doesn’t seem so. In 1982, Spaniards rated their freedom and control over their life at 5.9 out of 10, according to the World Values Survey, which is conducted by an international team of social scientists. In 2011, that figure was 6.7.

In 1978 there were only two television stations in Spain. In 1996, there were 12, and now there are more than 100. Spain is among the top 10 countries in terms of the number of people who have taken part in a demonstration, and in 2014 it topped Europe in this category.

Other figures also show how much progress Spain has made in the last 40 years. First, Spain is richer: average income per adult, for example, has soared from €19,000 in 1980 to €29,000 in 2016, with purchasing power parity taken into account, while average wealth per adult rose from €86,000 to €174,000 over the same period.

Health has also improved, with life expectancy up from 74 years in 1978 to 82 in 2011. In addition, health spending tripled from €1,200 per person in 1995 to €3,000 in 2015.

Meanwhile, education spending rose from 2.9% of GDP in 1980 to 4.3% of GPD in 2013.

In 1990, just 15% of deputies in the Spanish Congress were female, while that number is now 39%. The belief that homosexuality is unacceptable fell from 54% in 1982 to just 8% in 2011; for divorce, those figures were 28% and 5% percent respectively over the same period.

English version by George Mills.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario