What divides RBI and MoF

In a modern, middle-income, growing country, high real interest rates hurt the economy — and the people

Demonetisation led to considerable uncertainty increase in the economy and as correctly forecast by the RBI Board. (Illustration by C R Sasikumar)

The immediate Ministry of Finance (MoF) -RBI crisis has passed, and hopefully will not return. As many others have noted, the time has come for the two sides to talk, and communicate. In ‘Whose RBI is it?’ (IE, November 3) I had documented some large inconsistencies in the RBI/MPC’s policies over the last two years. These inconsistencies led to the MPC systematically raising real policy rates beyond its own stated and desired levels of 1.25 per cent. We noted that the real rate had averaged close to 2.5 per cent since October 2016.

Most central banks err on the side of caution — excessive caution means real policy rates 50 bp above target. In MPC India, excess real policy rates have averaged more than double the maximum “error”.

There is much discussion, perhaps even the conclusion, by most economists that the dispute is about the MoF wanting the RBI to part with some of its excess reserves. It is true that there is disagreement, and most reasonable economists believe that there are differences in views, and that it is common sense to resolve these differences. Indeed, there was a lot of debate on this issue even before Urjit Patel became governor of RBI in September 2016 — most notably, an open dispute between two good-friends, joint paper colleagues, and colleagues in government, Raghuram Rajan and Arvind Subramanian. The latter believed that the RBI should part with some of its excess reserves, and mostly for the reason that reserves were in excess of conventional global norms. Governor Rajan disagreed. What is so different today? Nothing. So, why the angst?

Like debt management by the RBI or MoF, this debate will continue. (One notable fact: Most recent RBI governors have argued for debt management outside of the central bank, as in most parts of the world, when they are not at the RBI. As soon as they become governors, their views change.)

Unfortunately, normal disagreements are being twisted into a debate about central bank independence. This is just plain wrong, and disingenuous. There is a news report titled ‘IL&FS crisis: This subsidiary ran business without capital for 3 years’ (Business Standard, November 1, 2017). This report hints at the RBI not performing its regulatory duties with excessive inter-group lending by ILFS. This issue needs open discussion rather than the false conclusion that any questioning of anything substantive is an infringement on central bank independence.

Such disagreements do nothing to improve communication between the central bank and the MoF and the public. Is this the new normal for India or will we get back to the old normal after the general election? I like the old normal — where issues are debated, questions are raised and clarity achieved, even without universal consensus.

I believe an important contributor to the RBI-MoF divide started to occur sometime in early 2017. My interpretation of the discord sequence is as follows. Demonetisation led to considerable uncertainty increase in the economy and as correctly forecast by the RBI Board in its approval note dated November 7, 2016, demonetisation was expected to have a “short-term negative effect on the GDP for the current year”. It did, and inflation also fell, real rates rose sharply, and the RBI did not respond by cutting rates. Growth slowed down, and discord developed. The previous article had documented the rise and rise of real rates; this article documents the rise, and rise, of positive MPC inflation forecast errors. And there is a definite link in the forecast-high-inflation-and-achieve-high-real-rates equation.

In their first three meetings post demonetisation (December 2016, February and April 2017), the MPC felt that inflation would accelerate from the 4.4 and 4.2 per cent inflation rate (observed in September-October 2016) to 4.8 per cent in 2017Q1. I have yet to find a single economist who has claimed (in writing) that the immediate aftermath of demonetisation (or any significant uncertainty-increasing policy in the world) would be to cause a significant jump in inflation. Note also that experts at the RBI/MPC were (correctly) anticipating a short-term negative effect on output. Their conclusion: Output would decline, but inflation would accelerate! Most economists in India (outside of the MPC) were forecasting both a decline in output and in inflation.

At the April meeting, the RBI still did not believe its forecast of declining GDP growth (which declined to 5.8 per cent in April-June 2017), and maintained its April-June 2017 inflation forecast at 4.4 per cent. Actual y-o-y inflation in April-June 2017 was 2.2 per cent.

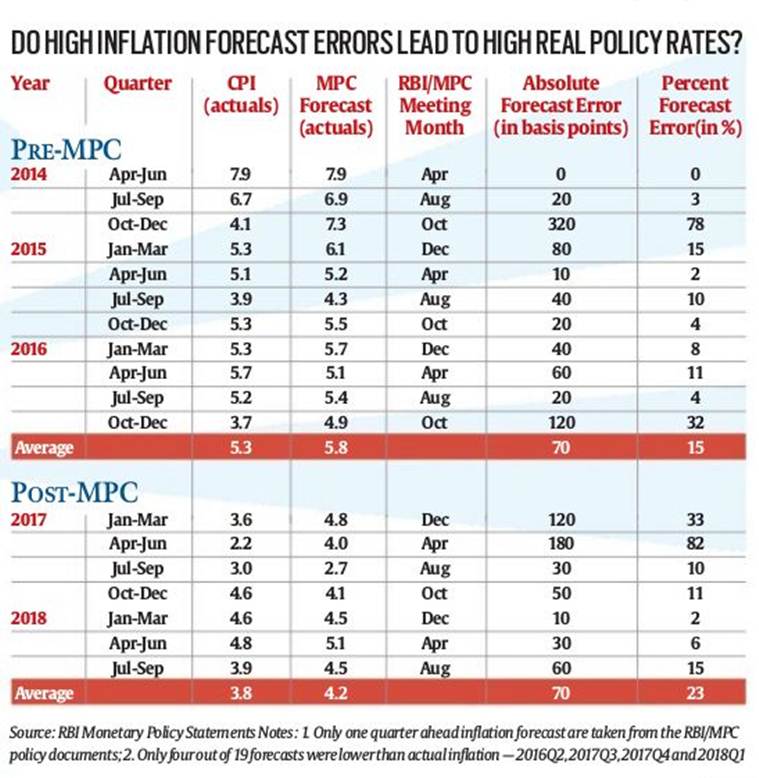

The point about this detailed analysis (see table, which reports on one-quarter ahead forecast errors for 19 quarters since April 2014) of MPC policy is to underline the fact that the RBI/MPC experts have systematically forecast too-high inflation — and that this forecast of too-high inflation has led it to recommend, and implement too-high real policy rates. This has had the expected negative effect on GDP growth and, therefore, depressed tax revenues and depressed fiscal spending — factors which the RBI and MoF should be concerned about.

Note that the assumption is that the Narendra Modi government wants to maintain fiscal discipline. Of course, the Modi government could go on a spending spree financed by an expanding deficit. But the MoF has made clear that it does not intend to do that, and it hasn’t done that — and too late now since it is just five months before election time.

The real reason for the MoF/RBI discord is the fact that the MoF feels that the RBI-led MPC has not conducted monetary policy according to its own RBI/MPC criteria and, hence caused damage to the political economy in this election year? In my article last week, I had documented that the RBI/MPC had implemented the third-highest real policy rates in the world, and done so for the last three years. And that they further increased real policy rates by 50 bp in two back-to-back increases in June and August 2018. And all on the back of highly questionable (and empirically quite bad) forecasts of inflation.

The table also reports on the forecast errors pre- and post- MPC. In the pre-MPC period, the average per cent forecast error was 15 per cent, that is, on a base of 4 per cent inflation, that is a one-quarter forecast error of 60 bp. Post-MPC (post Sept 2016) has (unexpectedly?) delivered a forecast error 50 per cent greater than pre-MPC — an average forecast error of 23 per cent, or, on a base of 4 per cent inflation, the MPC has systematically estimated inflation to be nearly 1 percentage point (actually 0.92 per cent) higher than actual.

This week marks the second anniversary of demonetisation. Besides all cash being returned to the system, there is no argument that the demonetisation attackers have against it. Proof for their conclusion is obtained from the fact that the media experts claim that cash today is higher than November 8, 2016 — hence, demonetisation was a failure. No reasonable economist has yet stated that the transactions demand for cash has a zero elasticity of demand. If incomes (GDP) double, cash demand doubles. Between 2004/5 and 2015/16, nominal GDP grew at a CAGR of 13.4 per cent per annum; cash in circulation increased at a virtually identical CAGR of 13.7 per cent.

In the 11 quarters since pre-demonetisation September 2016 to September 2018, cash has increased by 8.3 per cent and nominal GDP is estimated to have increased by 23 per cent — a cash-income elasticity of one-third the historical average. Yet, Opposition experts claim that demonetisation had no effect on cash demand.

The economy, the poor, the SMEs, the farmers are hurt far more by erroneously high real rates than most factors ostensibly causing the present rift between the RBI and MoF — theoretical central bank independence, adherence to Basel norms, or the sharing of RBI “excess” reserves.

The writer is contributing editor, The Indian Express and part-time member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council. Views are personal

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

More From Surjit S Bhalla

- Whose RBI is it?Genuine independence of a central bank has to be earned the old-fashioned way — by performance...

- Jobs and the pre-election yearConventional wisdom of no job growth in 2017-18 is found to be a gross under-estimate by a correct application and interpretation of household survey data…

- Scalding oil, sliding rupeeSometimes a crisis is brought on by faulty analysis; at others, by poor politics. The proper response to a crisis, however caused, is to change…

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario