Whose RBI is it?

Genuine independence of a central bank has to be earned the old-fashioned way — by performance.

(Illustration: CR Sasikumar)

To argue for the central bank’s independence is to argue for motherhood — we all should, and do, believe in it. But does that mean that there should be no checks and balances on the regulator? If there are none, then the impossible question arises — who will regulate the regulator? And how can the demand for independence be assessed? Here, an old ad by former stockbroking firm E F Hutton from the US (in the mid-1980s) is helpful. The simple punchline of the ad was as follows: We make money the old-fashioned way — we earn it!

Analogously, a central bank can earn respect through performance. But how does one measure performance? In the present Mexican stand-off between the RBI and Ministry of Finance (MoF), legitimate questions have been raised about the performance of both protagonists. But what underlies this tension, or open disagreement?

In the heated discussion about the RBI’s quest for independence, very few analysts have pointed out the role of the RBI in affecting the economy through its policies on interest rates. I understand that technically interest rate decision making is handled by an independent agency within the RBI (the Monetary Policy Committee, MPC) and not by the RBI per se. Thankfully, Viral Acharya does not hide behind this technicality. His speech, absent the polemics, contains an excellent discussion surrounding the concept and practice of bank independence. He discusses the effects of the economy of a responsible central bank — from bank independence, to inflation, to financing of the fiscal deficit, to interest rates.

As an economist, it is my privilege, and independence, to disagree with substantial portions of Acharya’s substantive comments on the facts pertaining to the effects of RBI’s interest rate policies on the economy. If these policies have had an adverse effect on inclusive growth, without contributing much to the lowering of inflation, then we may want to think about this reality being the real McCoy, the raison d’etre for the differences between the government and the RBI.

If there is one criticism I have against the academic portion in Acharya’s speech, it is that he speaks with the force of someone who believes he is 100 per cent right. That is okay, and expected, of a politician. But not of an academic, or an academic policy maker. For example, Acharya forgets to mention that there are reasoned economists and policy-makers — for example, former Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian — who have a different take (than the RBI) on the rules for the transfer of RBI’s surplus to the government. Nor does he mention even one critic of the formation of the MPC. He forgets to note that many of the experts he cites, and does not cite, do not believe that the MPC was a good idea. He forgets to note that New Zealand, which started the MPC movement, is now the first country to abolish it. In addition, Acharya cites the example of Paul Volcker defying President Ronald Reagan by keeping real interest rates high to contain inflation. He forgets to mention that for three years (1979-1981) the US had experienced double-digit inflation and hence it was necessary to keep real interest rates high.

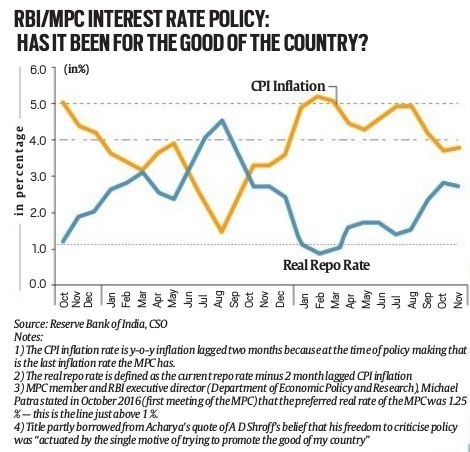

The real question, which I will address in this and a subsequent article, is the RBI’s policy on very high real interest rates necessary to achieve the objective of either containment of inflation or in achievement of potential GDP growth. I will present all the evidence to decide whether, in the words of A D Shroff, the RBI interest rate policy has been for the “good of the country”.

Most of the problems plaguing the Indian economy — liquidity, NBFCs, bank NPAs to name a few — will not be solved by the RBI’s following a constructive interest policy. But the problems would be much less. Monetary policy is about both the price of money, and the quantity of money (liquidity). The

primary concern of the central bank should be inflation. If inflation is high, almost any high interest rate policy (as that of Volcker’s in the US) is justified. The question remains: What justifies the high interest rate policy pursued by the RBI, with average inflation at 3.8 per cent for the last 24 months, and 4.3 per cent for the last 36 months?

In the very first MPC meeting chaired by Urjit Patel in early October 2016, the MPC cut the repo rate from 6.25 to 6.0 per cent. The last three inflation numbers available to the MPC, for June, July and August, were 5.8 per cent, 6.1 per cent and 5 per cent, respectively.

The MPC gave the following reason for the rate cut: Based on the August data, the real repo rate was now 25 bp above what the MPC deemed to be the “target” real rate of 1.25 per cent (6.5 per cent repo minus 5 per cent inflation). Hence, the rate cut of 25 bp to bring the real repo rate in line with the target of the MPC. Until this MPC decision, the belief was that the RBI was targeting a real repo rate of 1.75 per cent (mid-point of Governor Raghuram Rajan’s range of 1.5-2 per cent).

The chart shows the evolution of the real rate since October 2016 (using the MPC definition). Several facts are worth noting. First, in the 24 months since October 2016, the year-on-year inflation rate has averaged 3.9 per cent, the nominal repo rate 6.2 per cent, and the real repo rate 2.3 per cent. Only in three of these 25 months has the real repo rate averaged below the MPC target of 1.2 per cent — an average of 0.9 per cent for the three months, January-March 2018. For the rest of the time, the real repo rate has averaged 2.5 per cent, and this average is twice the MPC’s stated target.

In the last 36 months, the real rate has averaged 2 per cent; the last 24 months, 2.4 per cent. This with drought (in 2015/16), demonetisation in 2016-17 and the introduction of GST, 2017-18. Any justification for pursuing the third highest real rate in the world?

Markets are not a random walk, but feed on perceptions and communication. When the MPC announced, boldly and for the world to know, that it was targeting a real repo rate of 1.25 per cent, market participants (and presumably the MoF) took their policy conclusion at face value (as they should). This belief that the MPC would follow its original statement (sin?) of real rates led to consequences.

Domestic and foreign investors bought government securities in the belief that given its own statements, the RBI would cut policy rates. By doubling real rates, and implementing the third-highest real rate of any modern economy (behind Brazil and Russia), the MPC ensured that NPA assets will worsen over time (the banks now had bond losses on top of operational and corruption losses). Foreign investors fled, unable to rationalise RBI policies on interest rates — the same investors Acharya, via his speech, wants to cultivate and attract, and the same investors he warned would punish threats to RBI’s independence.

When oil prices started to rise, India faced a current account financing crisis — $ 25 billion of debt funds came in last year, and in 2018, close to $10 billion has left our shores. The difference is close to the current $35

billion current account deficit financing problem.

billion current account deficit financing problem.

High real rates slow investment, hurt inclusive growth, worsen bank NPAs — if inflation is low, then why should the economy pay a price? What the RBI has to show is that such high rates (again third highest in the world for the last 24 months) were necessary to achieve low inflation — neither the MPC, nor the RBI, has ever communicated this fact, let alone convincingly communicated it.

The point is simple — the interest rate decision is one of the most important decisions made by any central bank; it is their primary responsibility. In a subsequent article, I will discuss the large, and systematic, errors made by the RBI in its inflation forecasts, something that forms the basis of the decision of the MPC. And in making these forecasts, and making wrong policy, there seems to be zero accountability. This the real accountability that we should be concerned with.

The writer is contributing editor, The Indian Express and part-time member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council. Views are personal

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App

More From Surjit S Bhalla

- Jobs and the pre-election yearConventional wisdom of no job growth in 2017-18 is found to be a gross under-estimate by a correct application and interpretation of household survey data…

- Scalding oil, sliding rupeeSometimes a crisis is brought on by faulty analysis; at others, by poor politics. The proper response to a crisis, however caused, is to change…

- Pro-women, pro-poorIndia may have just witnessed the best four years of inclusive growth, thanks to the Centre’s sanitation programme..

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario